Most reviews of opera recordings don’t need preambles, but this one (sort of) does: Handel’s Serse (or Xerxes) disappeared from opera stages from its failed 1738 premiere (five performances and then nothing) until 1924. A man named Oskar Hagen discovered it and arranged a vocal score to be performed at the then four-year-old Göttingen Festival. What to do with such antiques was the question, and Hagen’s answer was pretty awful: arias were given to characters other than for whom they were composed and placed in different spots in the score. At least a half-dozen arias were eliminated and others shortened. The great Handel scholar Winton Dean refers to the end result as a “grinning parody”.

Xerxes received its first recording (off the air, I believe), from La Piccolo Scala in 1962. At the same time, in Germany, musicologist Rudolf Steglich had been working on Handel’s autograph score. He listed Handel’s preferred cuts and noted that most were stylistic: what had been de rigueur in opera buffa and grand Italian opera (long form, da capo arias) were, now late in Handel’s career, replaced by “songs”, many short and pithy, the most famous of which is the opener, “Ombra mai fu”, certainly one of the world’s most familiar operatic tunes. (There are still many da capos but their mid-sections are shorter.) Moreover, and I won’t delve any more deeply into this, it is an aria to a lovely plane tree, and as such it has been seen as the whimsical King’s introductory whimsy. However, one might also realize that King Xerxes, in the mid-day Persian sun, may have found great relief in the tree’s shade. A whimsical, sensitive despot is worth knowing.

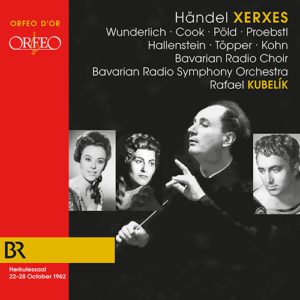

And Steglich used a German translation. When you realize that Thomas Beecham’s maddening, epic reworking of Messiah was foisted upon an unknowing public almost three years prior to this recording, Maestro Rafael Kubelik’s rendering of Xerxes–albeit auf Deutsch–is practically “enlightened”. No lengthy ritards at the close of arias, very little vibrato from the strings, some embellishments from the singers. No, we cannot unhear the remarkable “HIP” readings by McGegan, Bolton, Mackerras, and others, but Kubelik’s is entirely valid–sort of.

The roles of Xerxes and his brother Arsamene were written for a castrato and female contralto, and here we get two tenors, the first of whom, I’d guess, was part of the raison d’être for the recording. Fritz Wunderlich, just into his 30s, had taken the German opera houses by storm. With Frankfurt, Freiburg, and Stuttgart already under his belt, he sang Strauss’ Die Schweigsame Frau at the Salzburg Festival in 1959 and scored a brilliant success.

He had never sung Xerxes prior to this recording, although he was familiar with “early” music and had sung in Bach’s Passions. Kubelik immediately found him astonishing–the voice utterly beautiful, diction perfect, mastery of both legato and coloratura. Please, hear for yourself: this is such stunning singing that the vague antediluvian-ness of it all is not bothersome.

The rest of the cast is better than we have any reason to hope for as well: Unknowns to me are American soprano Jean Cook, a sweet Romilda, but nothing to write home about, and Naan Pöld, a fine German oratorio tenor as Arsamene. Ingeborg Hallenstein’s Atalanta has plenty of passion, and her flights into the vocal stratosphere–a high-F at one point–dazzle. Amastre is mezzo Hertha Töpper, so familiar and so routine from endless German recordings from the ‘60s. Karl Christian Kohn and Max Proebstl are fine as General and Comic Servant to Xerxes.

Sound is remarkable for its time. No, this shouldn’t be your only recording of this fine work, but if you do without Wunderlich, you are missing a great deal.