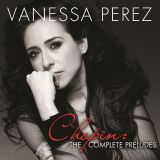

I first heard pianist Vanessa Perez’s Chopin on a 2005 VAI release that included all four Ballades, and was struck by her excellent technique and passionate temperament, as well as by her impulsive, sometimes cavalier approach to the text. Her all-Chopin Telarc debut featuring the complete Preludes, the Barcarolle, and the Fantasie largely confirms my earlier impression.

Whatever virtues Perez has as a colorist are compromised by a slightly boxy and monochrome recording that turns climaxes brittle and exaggerate the pianist’s foot stomping. In fact, older stereo analogue recordings of the Preludes by Ivan Moravec (VAI) and Jeanne-Marie Darré (Vanguard) prove far superior sonically.

On the surface, it’s easy to appreciate Perez’s unfettered, subjective way with the Op. 28 Preludes, with their contrasting characterizations and dramatic mood swings, but they tend to draw more attention to the pianist than to the composer. The first prelude’s bass line and inner parts, for example, take a back seat to Perez’s nearly exclusive focus on the top line melody. Her slow, uneventful No. 2 glides over the jarring dissonances. No. 3’s rapid left-hand arpeggios are poised and clean, albeit without the shapely refinement of Moravec or Tharaud.

One would think that a fireball like Perez would milk No. 4, but she plays it rather dutifully, in contrast to Pollini’s highly inflected version. She begins No. 5 with a swan-dive fermata, and misjudges Chopin’s cross-rhythmic part-writing by rushing and blurring certain phrase groupings. No. 6’s tiny hairpins and accelerandos are fidgety rather than expressive, and not so well contoured as Bolet’s more eloquent rounding off of phrases. No. 8 is assured and passionate, notwithstanding a few gauche accents.

The difference between her rhapsodic No. 11 and Tharaud’s is that the latter’s left-hand underpinning provides a stronger, deeper anchor. Other drawbacks include a C minor (No. 20) Prelude that is too slow for the slight rhythmic distensions to make sense, and the speedy, indistinct left-hand work in No. 24. Perez parks the Op. 45 Prelude in neutral, leaving poetry and narrative flow to more convincing rivals that are alternately slow (Ohlsson), fast (Argerich), and in-between (Michelangeli). The F minor Fantasy wavers between clunky (the opening page) and crass (the overpedalled climaxes, and the lack of long-spun lines in the manner of pianists so disparate as Arrau and Rubinstein).

Perez fares better in the Barcarolle, with her well-judged pacing and assiduous transitions between sections. Still, you’ll find higher degrees of finesse and lyrical eloquence from Moravec, Hamelin, Rubinstein (especially his live 1964 Moscow version), François, and Kempff. As for the Op. 28 Preludes, Perez faces considerable competition on all sides, from classicists (Pollini/DG; Schein/MSR; Ohlsson/Hyperion) to individualists (Sokolov/Naïve; Katsaris/Sony; Arrau/Philips).