Adelaide di Borgogna was Rossini’s 25th opera, debuted in Rome in 1817. Said to have been written without much care in three weeks, with some additional music (and secco recitatives, which Rossini had otherwise dispensed with in his Neapolitan operas) by composer Michael Carafa, it was not a particular success, and virtually disappeared, even from Italy, after 1825.

The overture is taken from the composer’s first opera, La cambiale di matrimonio; parts of Almaviva’s difficult final aria from Barbiere show up in an aria for the eponymous heroine (and Rossini had already re-used it in Cenerentola). It is hardly a great work—there’s much formulaic writing and the plot does not break any new ground. In 10th-century Italy, Adelaide (soprano), widow of the Italian King who was murdered by Berengario (bass), can reclaim the throne if she marries Berengario’s son, Adalberto (tenor). Ottone (mezzo-soprano), the German Emperor, luckily is in love with Adelaide, and he and his men defeat Berengario, leaving Adelaide and Ottone to marry.

This video, recorded during the 2011 Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro, makes somewhat of a case for the work, but not enough. To be sure, there are some fine moments, among them an opening number for chorus and Berengario that soon turns into a confrontation for Berengario, Adalberto, and Adelaide; an exciting soprano/mezzo duet and soprano/tenor duet that is exciting and catches the attention; and an equally exciting rondo-finale for mezzo.

Director/designer/costumer/lighting guy Pier’ Alli does not help. The costumes—and action—are updated to the mid-19th century, when Italy was attempting to unite: not in itself a bad idea. The opening tableau is promising—with the defeated and defeaters frozen in place, there is a back projection of a drawing of a fortress in geometric ruins (gimmicky but acceptable); sadly, this changes into a rainstorm for the second scene, which ends abruptly as Ottone enters, at which point it becomes a huge map of Italy’s north—although the puddles are still visible. Later, the soldiers carry modern umbrellas and use them as weapons, as if they were fencing. White handkerchiefs are meaninglessly waved during a chorus, after which the backdrop, broken into a half-dozen-or-more screens, shows people dancing while waving the aforementioned hankies.

At times the backdrops and sets are thoroughly realistic (a gigantic clock); at others, impressionism takes over. Adelaide, taken prisoner at the close of Act 1, is seen as a projection in a birdcage at the start of Act 2. There’s also a mixture of eras going on that keeps the audience guessing. Then, suddenly, a pair of beautiful, plush gold couches appear on what has been an empty stage, lit by a chandelier. These soon disappear. Where am I? What’s going on? When Ottone and Adelaide are about to begin their getting-to-love-you duet, they prance about; during the interlude between verses they do nothing. Nothing. No direction. And throughout, the characters are left on their own to deliver stock, hand-to-heart gestures. But the backdrop screens? Very active, fractured into a couple of dozen parts by the first-act finale.

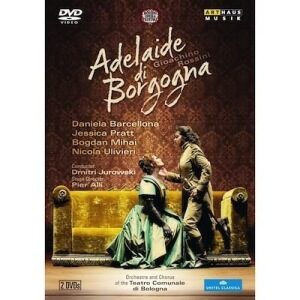

All the while, the singers sing splendidly. Soprano Jessica Pratt is lovely as Adelaide, fearless of coloratura and/or heights, her voice a bit thin at the start but gaining in stature as the opera progresses. By the second act she is tossing off roulades at all dynamic ranges and trying desperately to create a character. She’s wonderful. Equally good is Daniela Barcellona as Ottone. Lit and costumed in such a way that the top of her face is rarely visible under her helmet’s visor, she nonetheless makes quite an impression with her warm, agile voice and nobility of declaration. The voice seems less free at the bottom than I’ve heard her previously, but it does not mar the performance; it is Ottone who gets the final aria, not Adelaide.

A surprise entry is Bodgan Mihai, a tall, handsome tenor with a flexible, light voice with a solid center and fine technique as Adalberto. He really shines in his difficult if not memorable second-act aria. His acting is made up of lurching and swinging his right arm, the left one attached to his sword. Shame on the director. You would think that the role of the villainous Berengario would be juicy, but it is not, and his simple first-act aria is said to be by Carafa. Nonetheless, Nicola Ulivieri delivers his music with authority and excellent tone. All four principals shine in a quartet late in the opera, to a backdrop of rain, puddles, and open, Magritte-like umbrellas. As Berengario’s wife, who has a tedious aria di sorbetto before the second finale, mezzo Jeanette Fischer is good.

Conductor Dimitri Jurowski, younger brother to Vladimir, has been known for his work with the Russian masters—Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov—and, on the basis of this Rossini outing, that is where he will remain. Rossini is about forward propulsion and strong rhythms; Jurowski tends to slow down for emphasis (think of those Post-Romantic performances of Bach’s Passions) and has no feel for the bel canto idiom. (He has conducted Meyerbeer and some Baroque music also; you wonder if it was as poorly done.) The Bolognese forces play and sing well. Picture and sound are first rate and subtitles are in Italian, English, German, French, Spanish, Japanese, and Korean.

The only competition (a 1997 performance on Fonit Cetra has long disappeared) is from a CD-only set on Opera Rara; Majella Cullagh (sounding somewhat shrill) and Jennifer Larmore (superb) are in the Pratt and Barcellona roles and the conducting is better. But for video, you’ve got this one. As stupid as the direction is, there’s great singing to enjoy.