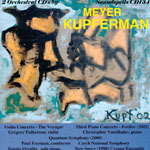

Volume 15 of Soundspells’ Meyer Kupferman series presents his orchestral music along with samplings of his chamber and instrumental compositions. Disc 1 opens with the Violin Concerto: Voyager (2001), a work that seemingly takes the Berg concerto as a point of departure. Like Berg, Kupferman adorns atonal harmonies in lush sonorities and highly coloristic effects (harp glissandos, etc.) to create a sense of “bitter” beauty throughout the music. Accordingly, the solo writing takes an ecstatic path rather than the more tortured trail adopted in many other “modern” atonal concertos. Violinist Gregory Fulkerson sounds completely in sympathy with the composer’s intentions and renders the solo part with great skill and care.

The sonic canvas changes drastically for New Space (1998) for oboe, violin, and guitar, where the loss of the orchestra, with its continuously variable timbres and sonorities, makes for hard listening. Even with the admittedly novel instrumental combination, the relentless barrage of dissonances soon begins to sound tiresome (there are few things more ugly than atonal oboe squawking). Still, the Cygnus Ensemble gives what sounds like an estimable performance of this challenging music, though I can’t imagine many people actually liking it.

Quantum Symphony (2000), with its powerful orchestral effects, blasts through the previously claustrophobic timbral atmosphere like a tornado. Kupferman displays considerable orchestral mastery in a terse and dramatic score that alternates passages of overwhelming density with those of exquisite delicacy. However, the music’s harsh aural character and violently dramatic sequences most readily bring to mind Grade-B horror film scores of the 1950s and ’60s–not that there’s anything especially wrong with that! Nevertheless, Paul Freeman and the Czech National Symphony deliver probing and vigorous performances of this and the other orchestral works in this collection.

Kupferman’s Third Piano Concerto, the toughest nut in this collection, opens Disc 2. Its agitated and tormented atmosphere, further intensified by the gnarly piano writing, sounds quite interesting–for the first few minutes. Unfortunately, little changes during the work’s 28 minutes, presented to us in one long, continuous track. Christopher Vassialiades offers an admirably cogent performance of the highly complex solo part, but it’s tough going despite his committed advocacy. He’s similarly adept, though, in the following Sonata Occulta that closes the program. This relatively mild work is mostly free from the modernist angularity of the concerto, and instead is drenched in the hyperbolic chromaticism of late Scriabin, to whose admirers I recommend the work accordingly. Soundspells’ recording is a touch distant and opaque in the orchestral works, clear and close in the chamber and instrumental pieces. Those interested in this sort of thing know who they are, and I also can recommend this to the very curious.