If you see this set of Shostakovich Piano Concertos in your local store (or favorite on-line site), don’t be put off by the label. This is not an historical release, even though Dutton has made its name mainly on its excellent transfers of antiquated material. In fact, Dutton has figuratively leap-frogged through time into the modern world of multi-channel SACD and, if the sonic evidence of this disc is anything to go by, it has a bright future.

Eliminating the center channel and subwoofer does nothing to diminish the spaciousness of the recording; frankly, both these extra speakers are largely unnecessary to produce a good soundstage, and only a few works might use the sub to good advantage. Dutton has company with other labels (notably, Chesky) who believe that 4.0 is the way to go, and it vitiates the tendency for engineers to spotlight the center in the usually vain attempt to “fix” the image or unnaturally amplify a soloist.

The vibrant sound on this disc (engineered by the omnipresent Tony Faulkner) still possesses too much “slap echo” in the rear speakers, as if to emphasize the fact that the recording hall has no audience and is therefore reverberant. This results in some blurring of the detail in the louder sections, but it is not too objectionable–and after all, what is the point of paying all that money for surround speakers if you don’t notice them?

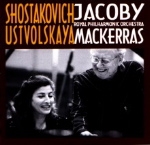

Musically, this set of Shostakovich piano concertos is completely satisfying and fits nicely alongside other well-regarded digital versions from Bronfman (Sony) and Leonskaja (Warner Apex). Since these works almost play themselves and need nothing more than precise execution and a bit of wit, they resist any radical interpretation. Ingrid Jacoby and Charles Mackerras don’t indulge, avoiding any chance at treacle, especially in the “romantic” Andante of the second concerto. These performances are as straightforward as they come and are successful and buoyant as a result. Solo trumpeter Crispian Steele-Perkins performs his role adequately in the first concerto, but not as brilliantly as Hakan Hardenberger, who cameos on Leif Ove Andsnes’ superlative version on EMI.

Galina Ustvolskaya’s one-movement concerto for piano, strings, and timpani makes for fascinating filler. Composed in 1946, its signature dotted rhythm forms the dominant motif of this succinct but intense and wide-ranging work in which the rhythm deconstructs into its essentials in quasi-minimalist fashion at the extended coda. This concerto not only recalls Shostakovich in the more brutal forthright sections (and in the painfully lyrical moments in the central sections), but it also harks back to Bartók in terms of orchestration, style, rhythmic vitality, and percussive piano writing. This is a worthwhile pairing that elevates this release far above the commonplace.