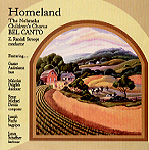

The Nebraska Children’s Chorus is one of the world’s outstanding choirs–on any level–and this program from its Bel Canto singers (the “most musically advanced” of the organization’s eight groups) shows both the astonishing versatility and the technical and musical prowess that defines today’s top children’s ensembles. The 47 choristers (membership begins at age 10) make a sound that’s not only mellifluous and pleasingly bright, but also well-balanced and nuanced, vibrant and powerful. Professional adult choirs have nothing on these singers–and if you’ve been out of touch with what’s happening in the youth choir movement during the last 10 or 15 years, you owe it to yourself to get re-acquainted. The high level of vocal skills and musicianship demanded by modern children’s choir repertoire is extraordinary–and the Nebraska ensemble, directed by Z. Randall Stroope, one of American choral music’s leading figures, takes us easily and impressively through works by Schütz, Lassus, and Brahms, as well as more demanding pieces by Elgar (The Snow, with its beautiful duo violin accompaniment) and Kodály (the wild, rhythmically exciting Turot Ëszik A Cigány).

One of the more delightful aspects of listening to children’s choir performances is discovering endlessly fascinating new repertoire–and we are not disappointed here. From Kis Svit–two folk-based pieces by Balazs Szunyugh–to Alice Tegnér’s Ave Maria, Herbert Brewer’s Magnificat in G, and Brent Michael Davids’ Zuni Sunrise Song (with its very sincere attempt at authentic Native American music sounds), we are treated to a consummately entertaining program and a fascinating musical tour of music from many countries–including Finland, Hungary, Italy, and French Canada. One of my favorite selections was O Pastorelle, Addio, from Giordano’s Andrea Chenier–but I also loved the high-B-flat ending of Donato’s Chi la Gagliarda, the unusual Amazing Grace tune (with bagpipe intro), conductor Stroope’s arrangement of Holst’s Homeland, and the concluding French Canadian Reel a’Bouche, arranged by Dalglish.

My only complaints about this recording–which tend to be consistent with my criticisms of most recordings in this genre–are relatively minor, but they have to do with the slightly distant, overly resonant sound, which makes us feel a bit more removed from the proceedings than we’d like to be and relegates the piano (on the few tracks where it appears) to an unnatural clinkiness. Also, there is virtually no information about the music–a significant omission, especially considering that many of these very worthy selections are not likely to be familiar to most listeners.