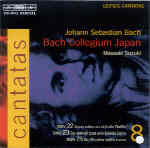

Volume 8 of the Bach Collegium Japan’s complete cycle of J.S. Bach’s cantatas begins a series devoted to works Bach composed throughout his tenure at Leipzig. In accordance with the series’ chronological format, this volume begins with Bach’s first Leipzig cantata (BWV 75), and follows with two works (BWV 22 & 23) he began earlier at Cöthen and completed after his arrival in Leipzig in 1723. While already remarkably adept at cantata form, Bach greatly matured due to the requirement of his new position that he produce at least one cantata every week.

While not as rousing or compositionally adventurous compared to the four cantatas offered in Volume 7, it’s clear that in all of the works presented here Bach has advanced to a new level of craftsmanship. The orchestration is noticeably more lush, as Bach often doubles and at times triples parts where previously only a single instrument sufficed. This additional instrumentation allowed Bach more expressive potential to heighten the impact of his subject. In Gerd Türk’s fourth-movement aria “Mein alles in allem, mein ewiges Gut” (My all in all, my eternal treasure) of BWV 22, the joy of his declaration is completely convincing, set against the steady interplay of strings accented by bassoon and organ continuo. Likewise in the first-movement duet of BWV 23 “Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn” (You true God and son of David) Bach’s use of a predominant oboe d’amore juxtaposed with strings, harpsichord (the first time Bach scores the instrument), and organ continuo beautifully introduces the melody as well as profoundly casts a melancholic introspective mood worthy of his most mature work.

BWV 75 (Die Elenden sollen essen) is a long work obviously intended to impress Bach’s new benefactors and congregation. Returning to the two-part theme he used so effectively in BWV 21, Bach creates a setting that’s two movements longer though (curiously) seven minutes shorter in performing time. Anyway, while in many ways more expertly crafted than BWV 21, BWV 75 is significantly duller. In not one instance does Bach even remotely take a risk. There are attractive moments, but they are nevertheless predictably formulaic. The threshold of the few dramatic moments is painfully narrow. However, when your laurels were as fresh as Bach’s were at this time, you certainly can’t be faulted for resting on them. Masaaki Suzuki and his colleagues do as much as possible and deliver a superior performance that would be difficult to surpass. Ultimately, this is one that will mostly appeal to Bach completists.