William Bolcom’s A View from the Bridge has the feel of an Americanized verismo opera, from its unvarnished portrayal of carnal passions, lust, jealously, betrayal, and vengeance, right down to its murderous final scene, after which the narrator proclaims the show’s over and bids the audience “Good night”. Based on the play by Arthur Miller, the story takes place in 1950’s Red Hook, Brooklyn, a neighborhood populated by Sicilian immigrants who maintain a strict code of honor and secrecy when it comes to aiding and abetting newer arrivals from the old country. Two such arrivals are brothers Marco and Rodolfo, cousins of Beatrice, who is married to longshoreman Eddie Carbone. Eddie respects the elder Marco, who is working to send money back to his hungry family in Sicily, but he’s greatly disturbed by the young, handsome Rodolfo’s interest in Catherine, Eddie’s beautiful niece. Eddie tries his best to discourage their budding relationship, as he is resistant to let the little girl he raised as his own free to become a woman–a woman for whom he secretly harbors desire. When Catherine announces her intention to marry Rodolfo, it sends Eddie into a near-murderous rage, and he commits the unpardonable sin of reporting the brothers to immigration authorities. Disgraced and friendless, Eddie nonetheless remains defiant, even as Marco, just released from jail, arrives to exact an apology. A fight ensues and Eddie dies, killed by his own knife.

The opera succeeds mainly on its compelling story, which Bolcom fleshes out with admirable ingenuity and skill. However, while primarily tonal, Bolcom’s music is more concerned with descriptive characterization (in the manner of Richard Strauss) and dramatic narrative than with melodic beauty (save for the few self-contained arias, which display Bolcom’s songwriting talent). But this is true of many an opera after the early 20th century, and like those, A View from the Bridge succeeds more at making an immediate visceral impact than at leaving a lasting musical impression with tunes that linger in the mind (as with Verdi, Puccini, or a great Broadway show). Still, Bolcom’s score, which incorporates pop and jazz elements as well as a variety of local effects, does hold the interest. Bolcom also employs a Greek chorus that comments on much of the proceedings, but this has the stilted effect of making the opera seem like a product of the 1950s rather than a contemporary creation.

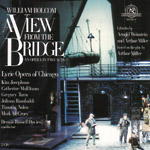

The performance, recorded live in Chicago (in disappointingly dry and boxy sound) features a fine cast. Kim Josephson has just the right mixture of tenderness, fierceness, and desperation in his singing to bring off the deeply frustrated Eddie. As Beatrice, Catherine Malfitano is emotionally convincing even though her tone occasionally takes on a hard edge. Gregory Turay makes the most of Rodolfo’s spinto tenor writing, including his gorgeous “City Lights” aria, while Juliana Rambaldi offers sweet-toned and impassioned singing as Catherine. Mark McCrory’s Marco is the strongest, most solidly-voiced performance of the bunch. Capping it off is conductor Dennis Russell Davies’ sensitive and vital conducting, which makes a strong case for this interesting new work. It’s not the “great American opera” some have been waiting for (for my money, that would be Porgy and Bess), but it’s well worth hearing nonetheless.