GLORIOUS JOHN AND THE BIG BAD BBC: A CAUTIONARY TALE

Once upon a time, in an island nation famous for its literature, theater, jurisprudence, empire building, and many other things (but not so much its music and musicians or its food, historically speaking at least), there lived a great conductor named Glorious John. His vision of the music he loved was very personal, his conducting inspirational but often wayward and undisciplined, and for various personal and artistic reasons he spent most of his career leading a provincial orchestra that never was better than second rate, and often much worse. Nevertheless, Glorious John loved them, and they loved him, and they did manage to make a few good records along with some less good ones, though even the less good ones were much better than they often achieved live, as the existing evidence clearly proves.

Glorious John’s record company, EMI, recognizing his genius as an interpreter, but also fully aware of the shortcomings of his orchestra, tried to arrange that most of the recordings he made of his core repertoire employed the best ensembles in the land under controlled, studio conditions. Unlike many other conductors, Glorious John did not suffer from any emotional or expressive inhibitions when an audience was not present, and benefited from the chance to correct mistakes or remake passages where he might have suffered a loss of control or have gotten carried away. Glorious John worked hard to make his recordings meet the highest international standards of the day, and he died leaving behind a very impressive and varied discography that sold well and has remained largely available over the years.

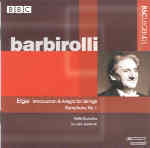

Of the many composers whose music he conducted with distinction, Glorious John probably loved Elgar the most. He left many fine recordings of Elgar’s major works, none greater than his last renditions of the First Symphony and the Introduction and Allegro for EMI (both pieces he also had previously recorded). Of course his numerous fans wished he could have done more, and many of them would listen to anything they could get their hands on regardless of its quality. Moreover, because Glorious John was so revered, just about anything he did could be (and was) tagged as “historically important”, usually out of (a) extra-musical considerations or (b) based on an exaggerated significance imputed to trivial differences between performances.

Now in the country that Glorious John lived, there was a big, fat, lazy, bureaucratic organization called the BBC, which owned the rights to many broadcast performances and thrived on a huge government subsidy arising from a tax on television sets. Realizing that it had a rich legacy of recordings, some of which were wonderful, and the majority of which were probably artistically worthless, the BBC decided to issue the ones by great artists such as Glorious John, regardless of the fact that many were really pretty bad or involved the same music that he had recorded commercially. The BBC also knew perfectly well that Glorious John never would have sanctioned the release of such largely inadequate material had he lived to have a say in the matter. Still, issuing such recordings cost very little, and since his fans would buy them anyway, the BBC began trotting out the CDs, many of which, however appalling, were welcomed by a musical press in his native land that enjoys promoting musical products on irrelevant national, historical, or personal grounds.

One of these CDs contained the two works by Elgar mentioned above: the First Symphony and the Introduction and Allegro, featuring Glorious John’s provincial orchestra. The performances dated from 1970, were sloppy (in the symphony, not even the attacks on the opening motto theme are together, and the scherzo almost spins completely out of control), indifferently played (with particularly scruffy strings), and captured in mediocre sound, but interpretively speaking were virtually identical to Glorious John’s superb EMI studio recordings of the same works. They said absolutely nothing new and yielded no unique insights of any significance. Nevertheless, the BBC released the CD, Glorious John’s fans bought it, the press in his native land praised it, and the only unhappy party was Glorious John’s record company, EMI.

Why was EMI unhappy? Because it had a serious investment in making those wonderful, authorized recordings, and EMI knew that it owned his best material. Despite all of its mistakes and the difficulties of the market, it had issued marvelous discs that upheld the quality standards that supported Glorious John’s claim to greatness, standards that both his fans and the BBC, for different reasons, refused to acknowledge. Those inferior, unauthorized broadcasts took away many customers and confused people new to classical music and to the legacy of Glorious John. Eventually, EMI saw no point in keeping its great recordings in print, and deleted them from its catalog. Future generations of music lovers, having access only to the inferior live performances, eventually came to believe that Glorious John wasn’t so glorious after all; they heard a sloppy, self-indulgent, second-rate talent rather than a great musician working at his best and most inspired, as in so many of those EMI issues. And the world of music was the poorer for it.

THE END