The history of Yehudi Menuhin’s recording of the Schumann Violin Concerto is probably as captivating as the actual performance he committed to disc in February 1938. As is well known to music historians, a political imbroglio between the British government and the Nazi regime in Germany ensued in 1937 over which country (and which violinist, Jelly d’Aranyi, Georg Kulenkampff or Mehuhin) would get the rights to the world premiere of this “rediscovered” concerto. The Nazis won that battle (but not the War); Kulenkampff gave the premiere and made the first recording (with Schmidt-Isserstedt) but, in each case, with massive cuts in the orchestral tuttis and other adaptations, thus rendering it a less-than-authentic memorial. Menuhin trumped them all, presenting the U.S. premiere of the “original version” with the St. Louis Symphony and then later making this recording.

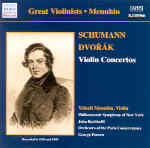

Menuhin’s traversal of both the Schumann and Dvorak concertos, among the few pieces he never re-recorded, were last released on CD in 1991 on Biddulph and EMI, respectively, and have been long out of print. Naxos has turned once again to Ward Marston for the restoration, and thus he too reprises the same role he played for the Biddulph release. Both discs of the Schumann possess fine transfers, although the second movement heard here does have some “groove noise” in the first minute or so of the second movement.

Unless you already have the Biddulph release in your collection, Menuhin’s Schumann is the only reason to purchase this budget disc. Rarely performed or recorded, this concerto nonetheless is stirring and evocative of Schumann’s broader orchestral writing, and Menuhin’s first-rate account (with a especially intense orchestral accompaniment in the first movement) is far more traditional and effective in conception than the more recent “experimental” thoughts offered by Kremer and Harnoncourt on Teldec, with their distended tempos.

The Dvorak is another matter altogether. Menuhin does not really sink his teeth into this music, whose lyrical beauty and racy rhythms seem to elude him at every turn. Parts of the middle of the third movement, for instance, sound like repetitive sawing back and forth without any sense of inflection or understanding. The soloist receives hardly any support from the listless, flabby playing of the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, conducted without much idiomatic flair by his teacher, Georges Enescu. Much to my amazement, even Naxos’ own annotator dismisses this performance as being second rate, admitting that neither Menuhin nor Enescu “bring anything special to the music.” Thus, as a document of this well-loved concerto, one is better served turning to more modern exemplars such as Suk, and more recently, Vengerov, Tetzlaff, and Suwanai.