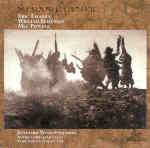

If it had been composed in 1896, Eric Ewazen’s Shadowcatcher might be a profound statement of sympathy to the Native American, or perhaps a piece outlining the composer’s fascination with this then-strange and exotic culture, shouldering the white man’s burden or ennobling the savage. Many composers, from Chadwick to Foote to Busoni, went through an “Indianist” period. Composed in 1996, Shadowcatcher (based on photographs of Edward Curtis, who either did the Native Americans a serious disservice or brought their culture to the public eye, depending on who you ask) sounds like Dances with Wolves redux, and shamelessly at that. It’s not the language that’s questionable–this kind of lush, very tonal sound is something Ewazen always has done well, and his brass writing is wonderful and well presented. The performance is good, an excellent pairing of the American Brass Quintet and the Juilliard Wind Ensemble under the careful, but not too-careful, baton of Mark Gould. It is not a bad piece, but rather an unforgivable idea. The subject matter, which leads to patronizing “Indian” dances in the final movement, or the prairie-evoking drum taps of the second, is almost so cheap as to be laughable–almost. It is not even possible to just take the music for its own sake, to judge it without the programmatic element, as these cheap shots are simply too obvious and overbearing as part of the insulting musical discourse.

William Schuman’s New England Triptych is his paean to Ives’ Three Places in New England in title only. He makes little attempt to invoke the master, instead creating music that is thoroughly his own, a stark, active-surface Americana–and it receives a decent if slightly flat-footed performance (José Serebrier’s recent outing on Naxos captures this music in a clearer, more crisply driven fashion). When it needs to be fast and furious, to turn on a dime, as in the “Chester Overture” movement, the Juilliard Wind Ensemble is right on the mark. Only in the more hymn-like chorale sections of “When Jesus Wept” does the ensemble lose some of its otherwise admirable collective continuity. Nevertheless the Juilliard players give Mel Powell’s brash, choppy (in the best sense) Capriccio for Band a stunningly on-target performance–full of life and direction, incisive, with a gorgeously played lyrical middle section. The piece is a profound romp, and conductor Gould understands that very well.