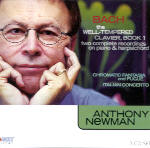

Anthony Newman first recorded Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier Book I on the harpsichord for CBS in the early 1970s. Nearly three decades later Newman brought the famous set of preludes and fugues back into the studio for two complete remakes: one with harpsichord, the other on a Yamaha concert grand piano. To illuminate the differences between instruments, the piano version features Carl Czerny’s long-discredited edition of the text. Czerny liberally applies tempo markings, articulations, phrasings, dynamics, occasional octave amplifications, and even note changes (the C major prelude’s notorious extra bar, for instance) that drive modern Bach scholars nuts. Such editorial graffiti supposedly represents how Czerny’s teacher Beethoven interpreted the “48”.

As it happens, the harpsichord brings out Newman’s freshest, most impulsive, and personalized playing. Indeed, some listeners might even proclaim his frilly octave couplings and proudly rolled chords as “Romantic” as anything Wanda Landowska set down on disc. Certain gestures might catch you off guard: for instance, Newman’s unusually brisk B minor prelude and a mandolin-like tremolo in place of the long trill at the G minor prelude’s outset.

I expected that when seated before a concert grand, Newman would follow Czerny’s directives to the proverbial max and really tap into the spirit of “inauthentic” Bach piano giants like Edwin Fischer and Samuel Feinberg. As it happens, he commands less authority at the piano than the harpsichord. Newman’s piano technique is essentially finger oriented, with little (if any) arm weight and no discernable power generated from the back muscles. He plays more on top of than into the keys, producing a flinty sonority that lacks heft and body. As a result, the intent and purpose behind Czerny’s phrasings and tempo fluctuations hardly register.

I can’t tell, for instance, if Newman genuinely wants the D minor prelude’s triplet figures to occasionally rush out of alignment, or if he intends to elongate some but not all of the C minor fugue subject’s final A-flats. Similarly, Newman’s slightly flustered left-hand scales in the A minor prelude yield to the rock-like security of Gulda, Hewitt, and even Fischer. On the other hand, Newman’s crisp and centered articulation in the B-flat prelude and fugue matches Gould at his spiky best. Shall we stay tuned for Book II?