Sometimes when you hear a recording that features rarely-recorded repertoire you end up wondering why more people don’t pay attention to it. This is one that leaves no doubt as to the pronounced neglect of the work at hand: Haydn’s Stabat Mater. Yes, it was “the first of his vocal works to achieve an international reputation”, according to H.C. Robbins Landon’s concise but informative notes, and it was favored by its original audiences in 1767–but those audiences had yet to hear the then-35-year-old composer’s late masses or oratorios. Mind you, this certainly isn’t neglible music by any means: most composers would be happy to have constructed an extended work with such a wealth of invention, fine tunes, and involving, challenging arias and choruses, all orchestrated with skill, economy, and an ear for color. However, as you listen you realize that while each individual section–the work is divided into 14–stands well on its own, the relentlessly dark, prayerful, heavy-hearted mood of this hymn is tough to sustain for more than an hour (this version clocks in at 60:22, and it’s not even the slowest on disc!), no matter how you mix the solos, duets, and choruses. In a word, size matters, and in my humble opinion a less ambitious treatment would have served both the listener’s interest and the functional requirements of the piece much more effectively. Several of the sections are between six and seven minutes long, including a tedious mezzo-soprano aria (No. 9) that nearly destroys what little momentum there is at this point.

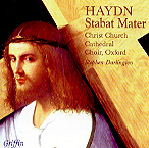

The performances–except for that murky mezzo aria–are really very fine, with sturdy, full-bodied, articulate, well-balanced choral singing, vibrant orchestral playing, and good solo work from soprano Jeni Bern, tenor Andrew Carwood, and bass Giles Underwood. And just because the text is sorrowful doesn’t mean that Haydn spared the singers a few virtuoso turns–for example the beautiful tenor/soprano duet “Sancta Mater” that ends with the soprano soaring brilliantly to the heights, and the furiously raging bass aria “Flammis orci”. Of course, Haydn gets plenty of chances to evoke and emote and paint pictures of the “mother of sorrows” standing “in tears beside the cross”–and conductor Stephen Darlington leads his forces in a conscientiously, reverently dramatic presentation of the score that will leave listeners no doubt as to the work’s somber, serious purpose. And you don’t have to pay very close attention to hear the promise of the even greater master–of symphony, string quartet, and vocal works–yet to come. The sound gives greatest focus to the solo singers, placing orchestra and chorus slightly behind without obscuring the instruments’ lovely ensemble quality or the choral detail.