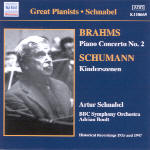

Artur Schnabel’s interpretations almost always reflect his forceful, inquiring musicianship and a higher, more flexible level of pianism than often accredited. His post-war Schumann Kinderszenen, however, leaves a strange taste. The livelier movements seem brusque, almost matter-of-fact in relation to Schnabel’s riper, more tenderly inflected way with Kind im Einschlummern, Der Dichter spricht, and the like. I miss Cortot’s quivering drama or Gieseking’s bejeweled symmetry, among my favorite (and rather disparate!) pre-LP-era Kinderszenens. Yet Schnabel has wonderful moments, as in his sublimely proportioned Traumerei. It sings out with ravishing shadings that never become garish in the manner of Horowitz’s famous encore renditions. Hear also how the pianist builds Wichtige Begebenheit from bottom to top, freeing the left-hand octaves from the tyranny of the barline, rather than letting the right-hand tune lead.

Given the luminous piano tone characterizing other Schnabel 1947 recordings like the Mozart A minor Rondo and Brahms G minor Rhapsody, I’m surprised by this Kinderszenen’s relatively dry and airless sonics. Mark Obert-Thorn’s remastering is comparable to Bryan Crimp’s more expensive APR edition. Similarly, Obert-Thorn effects a quieter, more detailed transfer of Schnabel’s 1935 Brahms B-flat Concerto than what’s offered on Pearl. The pianist fares best when the music is lyrical and expansive (listen to his gorgeous, urgent trills in the slow movement), but messes up quite a few of the first movement’s knotty chordal sequences (the opening cadenza, for one). In addition, many of the first and fourth movement octave passages fall by the wayside under Schnabel’s flustered hands. Granted, Schnabel doesn’t descend to the sloppy levels of Arthur Rubinstein or Elly Ney in their pre-war Brahms Seconds. Yet Wilhelm Backhaus’ 1939 traversal with Karl Böhm and the Staatskapelle Dresden offers comparable musicianship and far greater command of the notes, as well as a superior orchestra to Adrian Boult’s BBC ensemble. Jonathan Summers provides excellent, well-researched notes that rightfully place these performances in the context of their time.