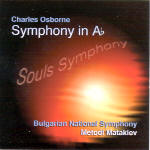

Charles Osborne is a distinguished composer of Jewish liturgical music, and the experience shows in this work, derived from an oratorio called Souls on Fire that explores the lives of seven seminal figures of the Hassidic movement. The music lacks the sort of structural focus and sense of drama typical of the traditional symphonic medium, but if you can imagine a sort of Hovanhess without the Far Eastern elements, then you’ll have a good sense of how this music sounds: basically slow, hymn-like, conventionally tonal, and very melodic. Listeners fond of a high level of dissonance and fans of the Second Viennese School or the Darmstadt crowd will hate it. Others might very well enjoy its simplicity and, well, prettiness. There’s more than a touch of Vaughan Williams in the opening Andante Maestoso, while other memorable moments include the fifth movement, with its appealing tunes set over swirling strings, the lovely Cantabile for flute and harp that opens the seventh movement, and the gentle Eastern European dance that winds its way through the eighth movement in various transformations.

There’s a sweetness about the piece that risks cloying, but Osborne avoids this pitfall by never putting his material under unnecessary strain. I was initially alarmed, for example, by the fact that the music of the opening returns as an Epilogue, hoping that it wouldn’t be forced into some sort of noisy, tacky, and vulgar apotheosis–but I needn’t have worried. Osborne’s quiet ending maintains the music’s fundamental dignity and devotional character up to the last bar. It’s easy to sneer at unchallenging, comparatively unsophisticated music such as this, but when all is said and done you very well may get more pleasure from it than from many other, more obviously “à la mode” creations of a spiritual bent by the likes of, say, Tavener or MacMillan. The Bulgarian National Symphony plays the piece with dedication, and the sonics, while admitting a fair amount of ambient hiss, capture the music with both clarity and warmth.