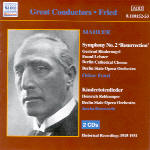

You’ve got to admire the chutzpah in attempting an acoustic recording in 1924 of Mahler’s Second Symphony, but that’s all you have to admire. Oskar Fried’s dully workmanlike performance, using an inevitably reduced orchestra, eliminates vast amounts of Mahler’s miraculously colored orchestral fabric while the recording barely captures what little remains. If you listen very carefully, you can just make out through the welter of surface noise the perfectly unremarkable first and second movements, a boringly slow scherzo (Scherchen and Klemperer do it so much better), Emmi Leisner’s very movingly sung but slackly conducted Urlicht (terrible brass playing), a couple of expansive (and none too well sustained, given the circumstances) tempos in the choral sections of the finale, and nothing else of special significance.

Oh yes, members of the “We Listen to Historical Orchestral Recordings for the String Portamento” fan club will find several notably ugly examples of this particular habit, especially in the second movement. Modern Mahler recordings, of course, use it too, invariably with greater finesse and taste than Fried’s grungy gang from the Berlin State Opera Orchestra. So if you’re thrilled by dimly reproduced, dynamically compressed melodic lines missing most of their supporting textures, and delight in noting minute tempo variations from one recording to the next (and are sufficiently experienced in Mahler 2 to make the comparisons), then you might hear something vaguely interesting in this particular musical approximation–for that is all that it is, the merest skeleton of the real thing, and anyone who tells you otherwise is hallucinating. That it makes any impression at all is a tribute to the ability of great music to survive adverse circumstances, in this case a working environment forcing on Fried choices more typical of a field surgeon performing emergency triage than a conductor interpreting a great symphony.

In fact, you might as well buy Klemperer’s or Walter’s stereo versions, if you don’t have them already. They knew and worked with Mahler too, and therefore command similar authority, for whatever that’s worth (not much, actually). Fried never claimed that his rendition was a reproduction of Mahler’s own, after all, and the evidence of Mahler’s own attitude toward Fried’s interpretations is, at best, ambiguous, even assuming that this particular effort, dating from nearly two decades after Fried’s first performance of the symphony, can still be said to represent the result of some discussion between composer and conductor (which of course it cannot). You may, however, get a kick out of some of the recording’s stranger anomalies, which allow you to amuse your friends by playing such games as “What key is the opening of the scherzo really in?” and “Is that strange noise Mahler’s rute part, or is someone knocking rhythmically on the studio door?” There’s no point in considering this performance in further detail. As an historical event, it has a certain value; musically, it has little if any.

Actually, all technical issues aside, there’s absolutely no inherent reason why early or first recordings of any unusual, outside-the-basic-repertory work should be especially distinguished musically regardless of the pedigree of the performers, though of course some truly are (like Mengelberg’s New York Philharmonic recording of Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben). You simply have to take them on a case-by-case basis. This is particularly true of large, complex pieces such as Mahler’s symphonies. Think of Walter’s sloppy and emotionally shallow 1938 first recording of the Ninth (which he subsequently regretted having made), or those incredibly scrappy and prosaic versions of the Third and Sixth by Charles Adler and the Vienna Symphony from the early ’50s, or Hans Rosbaud’s timid, excruciatingly played Seventh. Pioneering? Sure. Inspired? Definitely not. Had any of these recordings never existed, Mahler interpretation would be no poorer as a result. And so it is with Fried. Ward Marston has done what he could with the sound here. Even so, there’s still substantially more surface noise than music at any but the loudest moments. It’s like listening to a tinny transistor radio while someone runs a very loud vacuum cleaner right next to you.

On the other hand, Jascha Horenstein’s sensitive and passionate direction of the Kindertotenlieder (far more fluid of tempo than his later work) features some lovely wind playing from the same Berlin State Opera Orchestra, particularly in the first and third songs, made perfectly audible thanks to Marston’s admirably clear transfer. You can even catch a hint of the low celesta notes at the very end, something few modern recordings manage with any consistent degree of success. Heinrich Rehkemper’s aptly grave and world-weary delivery of the text suffers slightly from the voice’s lack of flexibility in negotiating “small notes” and ornaments (not that there are all that many) and from some unsteadiness of pitch in the upper register, but it’s still a noble performance (listen to him aristocratically roll those r’s in the last song), and it leaves a strongly positive impression. In any event, this truly is an important recording, not just for its self-evident musical accomplishments, but as the first example of Horenstein’s lifelong, if not always happy, engagement with Mahler’s music.

As for the other songs, these are only variably interesting, though Heinrich Schlusnus’ gripping Der Tamboursg’sell is certainly worth hearing. Grete Stückgold also sounds charming in her two numbers, but the big disappointment is Sarah Charles-Cahier’s offerings (Urlicht and Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen), particularly as she was one of Mahler’s singers in Vienna, appointed by him, and later featured in the posthumous premiere of Das Lied von der Erde under Walter in 1911. By 1930, the date of these sessions, she was clearly in decline. Still, it’s undeniably useful to have all of these early Mahler recordings gathered together at Naxos’ very reasonable price. Collectors of historical sound documents, Mahlerians, and fans of any of these artists will all find something to enjoy here. Others should proceed with caution and, particularly regarding the Second Symphony, with appropriately undemanding expectations. The rating applies only to the Kindertotenlieder. Technological limitations in the recording of the symphony, and the incalculable impact these may have had on the interpretation itself, place it beyond the bounds of normative comparison, both as performance and sound.