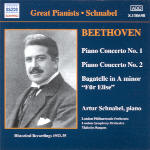

The passage of time hasn’t eroded the impact of these vital performances one iota since they first appeared in the early 1930s. Modern listeners, to be sure, might judge Malcolm Sargent’s accompaniments as being too casual for comfort in their frequently loose chording, held-back brass and slurpy string portamentos. Yet Schnabel’s contributions are intensely inflected and unfailingly alive at every turn. More often than not, gestures that sound unusually striking or quirky are simply explained by what Beethoven indicates in his scores. In the first concerto, for instance, Schnabel takes the slurs in the Rondo’s main theme on faith, and in the Second Concerto he adheres to Beethoven’s long pedal marking in the Adagio’s seraphic coda. The pianist’s “safety last” credo perhaps is best exemplified in his playing the First Concerto’s longer, more elaborate first-movement cadenza. Few modern pianists have matched Schnabel’s roguish brio in the Second Concerto’s outer movements, although I prefer the pianist’s 1946 remake (available on Testament) for its more playful Rondo and cleaner fingerwork in the knotty first-movement cadenza.

Many collectors will welcome Naxos’ budget-priced individual releases as an alternative to Pearl’s complete set of the Schnabel Beethoven Concertos. The main question is how Mark Obert-Thorn’s transfers for Naxos compare with Seth Winner’s for Pearl. On Naxos, the orchestra sounds less strident, warmer, and fuller of body. On Pearl, Schnabel’s piano tone gains in detail, sharpness of accent, and dynamic contrast. The differences are particularly telling once you A/B both transfers of Schnabel’s 1932 “Für Elise”, a more deliberate and carefully sculpted rendition than the pianist’s more familiar 1938 traversal. Naxos offers best value for your money. But if you opt for the more expensive Pearl edition, you also get rare live material unavailable elsewhere. Decisions, decisions! [5/27/2001]