Before Broadway and pop record charts, the best songwriters wrote tunes for singers with real–as opposed to electronically enhanced–voices. Ralph Vaughan Williams was one of the last of the masters of melody and mood and of the art of accompaniment-writing to take on this most underappreciated of musical forms. And as these rarely-heard works demonstrate, he left us a trove worthy of much greater attention by singers, chamber musicians, and listeners. Rather than follow the traditional solo voice/piano accompaniment structure, Vaughan Williams chose the violin (Two English Folksongs; Along the Field), an oboe (10 Blake Songs), a string trio (Merciless Beauty), or a string quartet and piano (On Wenlock Edge) for the solo voice’s accompanying partners. These often spare combinations not only require assured, persuasive central melodies, but also allow for interesting coloristic effects. Listen to how precisely and perfectly Vaughan Williams illuminates the words “sweet joy” in the first Blake song (Infant Joy), with just two notes.

And how we do appreciate the composer’s astute awareness that, while an oboe and voice make an attractive pair, listeners might not appreciate this sound alone for a 20-minute-long song cycle. So, he set several songs for voice alone–a decision that produced some of Vaughan Williams’ more inspired vocal writing. The unaccompanied The Divine Image has a strong and compelling melody like a hymn-tune, so pure and simple that no accompaniment could possibly improve it. In the Housman cycle Along the Field, Vaughan Williams needs just a few choice double stops by the violin to set the eerie mood for The half-moon westers low–and then, just with simple twists of melody and rhythm, he quickly changes the scene to the bright, lighthearted following song, In the morning. If there’s a drawback it’s that there’s not a lot of variety in writing style, from the earliest songs, written when the composer was in his 30s (On Wenlock Edge), to the Blake cycle, completed in the last year of his life. And, when compared with Britten’s more emotionally penetrating, far more brilliantly imagined works in the genre, these pieces seem all roses without the thorns–not always a bad thing, and certainly no hindrance to our ability to enjoy, love, and appreciate listening to them all.

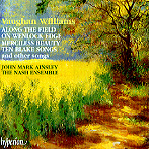

Tenor John Mark Ainsley has one of those real voices, and he uses it to supreme effect here, maximizing Vaughan Williams’ inspired lines and phrases to give near-pictorial life to the lovely poetry of Blake, Housman, and Chaucer. He’s especially experienced in English song-singing–he’s already recorded works of Britten, Finzi, Warlock, Ireland, and Quilter–and I can’t imagine a more sensitive, sweet-toned, clear-voiced interpreter to bring out the beauty of these artful, articulate creations. The sound fully supports and complements the desired intimate, chamber-music atmosphere–and the solo instrumentalists and ensemble are first rate. [2/16/2001]