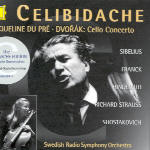

This is a set that even Celibidache fans may find hard to love. The playing of the Swedish Radio Symphony, with which the conductor gave regular concerts from 1965 to 1971, is subpar, even when compared with the hardly world-class Stuttgart Orchestra featured on the rest of Deutsche Grammophon’s Celibidache Edition. And Celidache’s interpretations offer no special insights, despite all the musical-mystical hype printed in the booklet notes (though we do get to hear his singing and groaning at climatic moments). The main draw for some collectors will be cellist Jacqueline du Pré, featured in the Dvorák Cello Concerto that constitutes the first disc. Du Pré gives a characteristic, highly emotive performance, one in which she pours out passion from her cello while letting not a few squeaks and sour notes slip by as she gets caught up in the heat of the moment. Celibidache manages to stay out of her way and keep the orchestral proceedings flowing smoothly. There are better performances, but du Pré fans won’t be disappointed. [Editor’s Note: This performance is also available on Teldec as a single disc, so collectors interested in this work alone can save some money and purchase accordingly].

Disc 2 gets off to a troubled start with a terribly gelatinous Franck D minor symphony, where Celibidache makes the first movement’s tremolo-drenched introduction so slow and heavy that you’d almost think you’re listening to the Liebestod from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. And despite the brooding and portentous lead-in, nothing really exciting happens in the rest of the movement, or, with the brass lost in the swampy orchestral balance, in the rest of the symphony either. The following Hindemith Mathis der Maler Symphony, featuring more normal tempos, is basically a run-of-the-mill performance that also suffers from soggy articulation in its outer movements and a serious lack of contrapuntal clarity (a function of the playing more than the recording).

Disc 3 begins with a big, boring, and bland rendition of the Sibelius Second Symphony, recorded in dry mono sound. The Fifth follows, in stereo, and actually has some interesting moments, like the carefully graded dynamics of the first movement’s development and the ringing horns in the “Thor’s hammer” theme of the finale. The last disc features an energetic, pulsing Don Juan and a suitably frolicking Till Eulenspiegel (a work duplicated from Celibadache’s Strauss box)–but so what? Still, there’s a gazillion better played and better recorded versions of these works available!

Lastly, Celibidache’s rhythmically tired, indifferently played Shostakovich Ninth has about as much sparkle as a bottle of flat seltzer. The overall recorded sound is merely broadcast quality, though with usually decent balances (except for the cello-dominated Dvorák, and the foam-engulfed Franck). The previous issues in DG’s Celibidache edition varied in their demands on your attention, especially those that were duplicated by EMI’s superior sounding and better played recordings with the Munich Philharmonic. But this one? Unless you’re a hard-core Celi devoteé, take a pass.