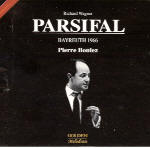

Wieland Wagner’s stripped-down, minimalist Bayreuth Festival staging of his grandfather’s Parsifal finally met its aural equivalent when Pierre Boulez first conducted the opera in 1966, and again in 1970. The 1970 Bayreuth performances were taped and released by Deutsche Grammophon. As an admirer of Boulez’s Wagner, I’ve long been curious about this 1966 Parsifal, tapes of which circulated in the live opera underground. Podium-wise, there’s not all that much difference between this and Boulez’s commercial version. You’ll find the same fleet tempos, horizontal continuity of texture (Boulez always has been a line guy, as opposed to chord guys like Karajan, Krauss, Knappertsbusch, and Solti), and tensile, unsentimental drama. By 1970, however, Boulez allows the set pieces and key transitional passages more breathing room. He enjoys a superior and more consistent if not ideal cast.

In 1966, the best singing comes from Gustav Neidlinger’s dark, menacing Klingsor, and the various squires in Act 1. Thomas Stewart’s not-too-tortured Amfortas, though, is heard to better advantage in the DG Boulez recording. By contrast, Josef Greindl’s authoritative Gurnemanz doesn’t match his younger self (the 1949 Richard Krauss Köln Radio broadcast), nor Hans Hotter’s or Ludwig Weber’s multi-dimensional portrayals. Kurt Böhme’s Titurel is hardly the ailing one, but who’s to refuse such vocal presence when you can get it?

Sandor Konya is not as vocally striking as 1970’s James King in the title role, but he’s every inch as committed and hooked into the text. As Kundry, however, Astrid Varnay’s big voice is alarmingly off form. She fares best while singing in her softer, mid-to-lower range, but her out-of-control high notes are pretty painful to endure, with one exception. As Kundry describes how she mocked Christ on the Cross, Varnay more-or-less nails that famous, cruelly exposed high B. Anja Silja also was working through a rough vocal patch at the time, and you can hear it in the way she sticks out among the Flowermaidens.

The inconsistent sonics present another drawback. Murky sound plagues the first two-thirds of Act 1 and all of Act 3, and seem to stem from multi-generational tape copies of a broadcast captured on home equipment. A professional-sounding source boasting superior orchestra/singer balances is spliced in after the transformation scene, beginning with Titurel’s first words, and continues from here to the end of the act, along with all of Act 2. No texts and translations are included.