It’s unfortunate that relatively few listeners will ever have heard Berlioz’s “other” masterpiece, the oratorio L’Enfance du Christ. Admittedly somewhat disjointed in its overall musical structure (its sections were composed over a period of years–middle, end, then beginning) and underdeveloped as a dramatic work, this 90-plus minute musical depiction of events immediately following the birth of Christ overcomes these potential flaws to register very agreeably on the ear and touches pleasantly on our affective and aesthetic senses as well. The three-part work displays many moments of magnificence–luscious orchestral writing, one of the more beautiful choruses in the Romantic repertoire, operatic-style solo vocal parts–and under its surface is an opera longing to break free. (Instead Berlioz devoted his operatic composition energies to Les Troyens in the years immediately following the premiere of the complete L’Enfance in 1854.) Nevertheless, L’Enfance possesses the qualities of good theatre–real characters, vivid scenes, moral conflict and triumph, adventure, colorful supporting cast (soldiers, shepherds, angels), scene-setting orchestral interludes, and great music.

The public and critical success of the chorus known as “The Shepherds’ Farewell”, which was written first (1850) and is often performed today as a self-contained piece, eventually led Berlioz to compose the surrounding movements, ultimately adding a beginning with Herod’s tormented deliberations, the intrigues of the soothsayers, Roman soldiers on the streets of Jerusalem questioning Herod’s behavior, and Herod’s decision to murder the innocents. In the following scene a gentle introduction leads to a lovely duet sung by Mary (soprano Susan Graham) and Joseph (baritone François Le Roux)–a real treasure and one of this performance’s highlights.

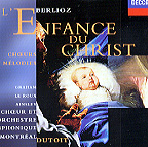

And speaking of the performance, Charles Dutoit leads his excellent cast of soloists, chorus, and orchestra with great care and graceful control–no rushing or pushing, allowing a certain sense of mystery to prevail in the atmosphere. This atmosphere is effectively enhanced by Simon Eadon’s tasteful engineering and the ideal acoustics of Montreal’s legendary St-Eustache Church. In addition to the performance’s convincing sincerity, it also conveys the conductor’s obvious relishment in Berlioz’s orchestral writing. It’s not a large orchestra and overall the score reflects a simplicity and often charming delicacy that we don’t usually associate with this composer. The program is filled out with several interesting but not exceptional works for chorus and two songs with orchestra. These rarely heard pieces will be of interest primarily to choral enthusiasts and Berlioz completists–and audiophiles will notice that these last are recorded with less clarity (especially the choruses) than the oratorio.