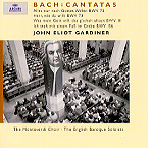

Disappointment has become a consistent feature of this ambitious but ultimately ill-advised Bach cantata series from John Eliot Gardiner and his Monteverdi Choir. This latest release comes from a church in Milan and features four cantatas composed for the “Third Sunday after Epiphany”. Sure enough, in an apparent nod to authenticity, Gardiner and his usually excellent choir and orchestra recorded all four works in late January of this year. But right from the start, from the opening chorus of Alles nur nach Gottes Willen, something is wrong: the balances between chorus and orchestra and among sections of the chorus are off, a disengaging and disorienting effect. You have to wonder: why drag all of these people all the way to Italy to record Bach when the result gives such an unnatural sense of acoustical perspective? In this kind of listening environment it’s hard to concentrate on the music and on the interpretations themselves. And although the performances are okay, that’s all they are. All the while when listening I thought, why did this fine group of musicians make this recording–was it just to fulfill a contract?–because nothing in it rises to a level that says “we’re committed to this music, we really have something to say and we’re saying it.” Besides sounding underrehearsed in the choruses, the performances suffer from Gardiner’s uncharacteristically halting leadership that leaves us puzzled about tempo choices and expressive mannerisms–including excessive punching of the words as if to shake us into acceptance of the creed “All only according to God’s will” in the opening chorus of BWV 72 and the clipped, march-style chorale in the same cantata.

Experienced Bach listeners will perk up at the opening sinfonia of BWV 156, a setting for oboe solo and strings of music Bach later used–and elaborated–in the slow movement of the F minor concerto for harpsichord. It’s one of the most famous of Bach tunes–but the liner notes refer only to “the simplicity of the oboe line” without mentioning the important link to the concerto. In the gorgeous tenor aria with chorale accompaniment (the second movement of BWV 156), soloist and chorus are strangely disconnected, as if singing in different rooms with different conductors. The major bright spot in all of this is Stephen Varcoe, who’s listed as a bass but is really a baritone. His lovely lyric voice and musicianly sense of nuance and phrase turns everything he sings to musical gold. Otherwise, this is another example of what can happen when even first rate musicians undertake a project on which they probably should have taken a pass.