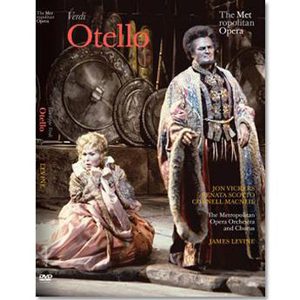

[A re-post from our archives, in memorial tribute to Renata Scotto, February 24, 1934–August 16, 2023]

Jon Vickers was, and remains, the greatest Peter Grimes and Otello I ever saw on stage. Both of these characters are tormented; critics and the public speak of “total commitment” but rarely get it with such deep-rooted feelings. While other great tenors–Peter Pears as Grimes, Placido Domingo as Otello–were riveting in these roles and offered “complete” portrayals, Vickers appears as if he’s ripping his own heart out. His wounds are so deep that you are tempted to avert your eyes. There becomes no separation of man and actor. (Each tenor’s undertaking is available on DVD; in the case of Domingo as Otello, at least four times.)

This Met production is by Franco Zeffirelli and was new in 1972; it is still good-looking and effective and not nearly as outrageous or flouncy as his later Traviatas or Turandot. The opening storm is powerful, the giant props in Act 2 imply grandeur and importance, the change from the first to the second scene of the third act is magnificently done with the entry of the Venetian ambassador as lavish as it should be.

Fabrizio Melano directed this 1978 revival, concentrating mostly on the three principals, and Kirk Browning directed for television, making utter sense of the textually complex, great third-act concertato, moving from wide-angle shots to a sickly, slow close-up of a lonely, murderous, out-of-his-mind Otello, mid-stage, on his throne.

Vickers was a complicated singer; rarely did he turn in a vocally flawless performance (when Domingo “took over” as the go-to Otello, the sheer Italianate beauty and accuracy of his singing were greatly welcomed and commented on). Vickers croons occasionally here; a bit of hoarseness sometimes enters, and he cracks on a climactic B-flat in Act 2–and turns it into a dramatically accurate point, by the way. But 90 percent of the time he is on top of his vocal game: the sheer heft of his voice in “Exultate…” and “Si pel ciel”, not to mention his denunciation of Desdemona, is terrifying. His movements are of a caged beast–I’m tempted to call it choreography.

He strides the stage–this Lion of Venice–in an animalistic manner. You want to weep for Domingo’s Moor; you fear Vickers and feel his fall from gentle lover in Act 1 (he takes the final five notes of the duet–the repeated A-flats–quietly) to insanely jealous madman.

Renata Scotto interprets Desdemona as no other singer I’ve ever heard or seen. Too often played as a victim/wimp-we-love (see Kiri Te Kanawa), here Desdemona is a woman of strength who can’t win; regal of bearing, she tries to fight back in Act 2 and even in Act 3, but realizes she’s doomed. We can see her fear, and more, we can see her trying to hide it. Her last-act Willow Song is almost a Mad Scene–she’s transported. The Ave Maria is gorgeous; in fact Scotto is in great voice throughout and she matches Vickers in acting skill.

Cornell MacNeil was a Met stalwart, a fine baritone with a spectacular, ringing top. Rarely a subtle actor, here he is at his best: perhaps the sense of occasion inspired him. The voice is in fine shape–he matches Vickers note-for-note in their duet, and in “Cassio’s Dream” his soft, insinuating singing is as smarmy as it is enchanting–and he moves (and leers) with snakelike grace. He actually looks conniving; this Iago is always thinking. It’s not exactly a luxurious sound, but this is a great Iago.

If you want luxury you must wait for the entrance in Act 3 of Lodovico, sung by a young James Morris. Jean Kraft, by the way, is the conflicted Emilia. James Levine, at his most potent and understanding (he adored Scotto), helps make this the dramatic event it is, with the fantastic Met Orchestra a seeming extension of his arm.

This was the first Met telecast (September 25, 1978) that I attempted to tape with my new RCA VCR, a technology that was younger-than-springtime at the time. I still have that error-laden, foggy, poor-reception tape (I did not have cable), but bless the Met for finally opening its archives and for restoring the now 33-year-old artifact to far-more-than-good standards, both visually and sonically. I saw one of this run of performances live as well and left the Met, as did a couple of thousand others, trembling. Watch this and you’ll see why. I love Domingo too, but this will be the only video Otello you’ll ever need: it’s the one that best captures the pity and sadness. [11/1/2011]