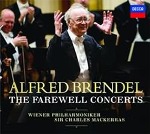

The works featured in Alfred Brendel’s orchestral and solo “farewell” concerts respectively held in Vienna and Hanover in December, 2008 offer repertoire already available in the pianist’s large discography, and in multiple versions, no less. Yet the performances differ enough to warrant serious comparison and discussion.

In Mozart’s K. 271 concerto, for example, Brendel takes a more lyrically caressing view of both the slow movement and the finale’s cantabile menuetto than in his three earlier recordings, yet his fingerwork in the outer movements proves a shade less pointed and incisive than before, especially in his superb first traversal for Vanguard. Furthermore, the live recording’s resonant patina somewhat pacifies the tart impact of the forward winds and discrete string vibrato that distinguished Charles Mackerras’ work with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra in Brendel’s most recent version.

As with his studio and live Salzburg recordings of the Haydn F minor Variations, Brendel’s valedictory interpretation is intense, well projected, and thoughtfully integrated. I wrote in detail how Brendel’s 2002 studio remake of Mozart’s K. 533/494 sonata improved upon its 1992 counterpart (type Q6410 in Search Reviews). Six years later the pianist plays the first movement a shade faster and lighter, and, in the finale, captures a music-box-like delicacy that eluded him in the studio yet manifested itself in concert.

Beethoven’s Op. 27 No. 1 fares best in the first movement’s Andante episodes and in the flexible, sensitively shaded Adagio con espressione. Elsewhere, the first-movement Presto is hardly the surging outburst it ought to be, while the Scherzo’s notes are dutifully presented minus the music’s underlying humor and carefree demeanor–and the rollicking Finale is foursquare and pedantic.

Brendel’s late-1980s studio Schubert B-flat sonata D. 960 represented a simpler, more organically nuanced advance over the pianist’s relatively fussy and overpointed 1972 traversal. Less detail and more “big picture” emerges from the distant sonic perspective of Brendel’s live 1997 Royal Festival Hall recording, along with the pianist’s palpable gift for dynamic projection (even up in the balcony, his softest playing registered with clarity and definition). By contrast, closer microphone placement brings fastidiously concerned details to the fore, such as the Scherzo’s subtle shifts in voicing between hands, and, in the Finale, marked contrasts between legato and detached phrases and meticulously articulated polyrhythms (the left-hand triplets against the duple-time right hand).

However, in the long first movement (Brendel, by the way, never opted for the exposition repeat) the pianist intones the opening theme and its C-sharp minor counterpart in the development section in darker, slightly more muted phrases than before, as if the music were playing itself without the intervention of an interpreter. Brendel’s slow movement remains a model of wistful serenity, even in the face of similar, more tonally alluring competition from Leif Ove Andsnes and Leon Fleisher.

The encores largely show Brendel at his best. Beethoven’s A major Op. 33 No. 4 Bagatelle gains ripeness and character over its similarly well-played yet relatively formal Philips digital studio counterpart. Brendel’s 1988 studio Schubert G-flat Impromptu regained a fullness of body and long-lined directness missing in his more emphatic 1971 version. So does the encore, with added rubato touches. Heard live, the Bach/Busoni chorale prelude must have made a mesmerizing, large-scaled impact, although repeated hearings actually show Brendel progressively slowing down his basic tempo. Brendel’s vocal grunts are consistently noticeable but not irritating. The pianist’s admirers, of course, will purchase this release as a matter of course, while general listeners should consider it for the Haydn, Mozart, and Schubert selections.