Acis & Galatea was Handel’s most popular work during the 18th century, and it is easy to understand why. The tunes are lovely, frequent, and easy; the work’s brevity, charming scoring, flights of vocal fancy, catchy rhythms, and nymphs and shepherds/”Monster Polypheme” personages and tragic, sentimental ending combine to make you feel alternately good, winsome, menaced, and sad. It’s a full package, seemingly without guile.

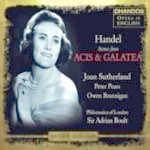

The re-release of the original Decca recording from 1960, in excellent sound, is most welcome. Other performances (as many as nine, I believe) have come and gone, but none has the glowing, personal stamp that Adrian Boult puts on the music, and three of the four soloists probably have never been bettered. Those of an utterly authentic bent will not approve of the da capo cuts, the disappearance of Coridon, or the leisurely tempos (the recitatives are positively lethargic), but by the time they’ve finished listening their love of great singing will have surpassed their love of historic accuracy.

At the performance’s center is Joan Sutherland at her youngest and most unadulterated, her diction admirable (it fell apart, I believe, in 1961), her tone almost unbearably beautiful. The trills in “Hush ye pretty warbling quire” still amaze and made me ask myself where else I’d heard that ornament so perfectly executed. The answer was “nowhere” and always has been (sorry, Selma Kurz fans); even Beverly Sills invariably began her trills on the wrong note.

If I had to nitpick I’d confess that while Sutherland can express “longing” she certainly has no right claiming either “great pains” or “fierce desire”, but who cares? She droops her way up to the first word of the recit “Oh! Didst thou know the pains of absent love”, but her singing of the following aria, “As when the dove”, is such an object lesson in taste, bel canto, and charm that the head spins. And she has all the pep you’d want for “Happy we”, surely the jolliest piece Handel ever composed.

In the same class is Peter Pears’ Acis. For a man whose voice was hardly beautiful, he sings “Love in her eyes sits playing” with a legato and melting tone that captivates, and he matches Sutherland beat for beat in “Happy we”. Owen Brannigan’s Polyphemus is grand-toned and impeccably enunciated and his coloratura is clean (after the first “I rage” or so). The role is a problem: Polyphemus is clearly a villain–he kills our hero–but there’s something comic and sad about him as well. But again, why overanalyze?

The first time I heard this recording 30-or-so years ago I immediately re-played “O ruddier than the cherry”–and I did so again with this new CD version. The Damon of David Galliver is in a different class from the rest–he’s an intelligent, sensitive singer who can’t quite hold the pitch and he barely gets away with the runs in his first aria.

That Boult has the feel of the piece is evident throughout; the dark warnings of the “Wretched lovers” chorus has real thrust; the trio “The flocks shall leave the mountains”, a glorious example of Handel’s ability to have characters expressing feelings at odds with one another, is truly menacing with Polyphemus’ interjections. The St. Anthony Singers and Philomusica of London are superb.

Yes, there are other fine performances of this work: Gardiner’s features a marvelous Anthony Rolfe-Johnson and enchanting Norma Burrowes; William Christie interestingly uses a female Damon (Handel approved it for a 1739 revival) and an otherwise splendid line-up; and Trevor Pinnock employs Mozart’s arrangement. But this one is sui generis. How nice to have it back! [11/30/2007]