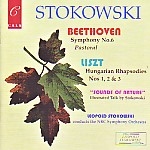

Not surprisingly, Leopold Stokowski’s recordings with the NBC Symphony have the orchestra sounding very different from the way it did for Toscanini, nowhere more so than in this sometimes weird Pastoral Symphony. The first movement, sans repeat, promises a fresh and lively interpretation. Woodwinds cut through the texture quite beautifully at the end of the exposition, though the oboes have more than a touch of vinegar in their tone. The scherzo, with its rustic horns, also is quite bouncy, making it all the sadder that the obligatory repeat is missing. Stoki’s handling of the storm has surprising transparency–along with some odd balances in favor of the bassoons, and reticent timpani (surely intentional–the sforzando attacks and softer rolls make them more “thundery” in a subliminal sort of way). The strings in the finale glow as only Stokowski could make them.

Then there’s the Scene by the Brook. It lasts more than 16 minutes, and not even Stokowski’s podium wizardry can make that tolerable. Sultry, sexy, languorous–yes. Beethoven? No. But the real treat is Stokowski’s illustrated talk about “music and nature”, where he explains that Beethoven’s imitative music should be heard as stylized and not literal. To illustrate, he plays the sound of an actual brook, real birds, and thunder, following this with Beethoven’s versions, and then superimposing the two simultaneously! It’s all so silly, but it’s delivered in such a deadpan, serious way that you’ll come away scratching your head in disbelief.

The three Hungarian Rhapsodies (logical couplings, right?) are wonderful, vintage Stokowski–totally reorchestrated, rhythms pulled about like taffy, boatloads of glitz and glamour–and it’s all about as authentic as a fluorescent velvet portrait of the Hungarian countryside. You’ll love it. The sonics are quite good mono for the early ’50s, a bit flat in terms of dynamics, but clear and relatively free of distortion. It’s interesting to compare the Beethoven to the recent, ghastly Pletnev on DG. Stokowski is every bit as perverse–maybe more so; but no matter how bizarre he gets there’s no question that in his way he’s still a servant of the music, illuminating it (at least most of the time) in ways we never would have dreamed possible. There’s always method to his madness, and that’s what makes him loveable even when he’s being outrageous.