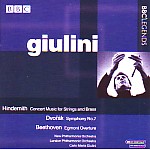

There is a fundamental illogic to the commonly heard assertion that conductors who ignore a composer’s clear tempo instructions and play everything within a movement at the same speed are somehow being “architectural”. The fact is that a movement written in distinct tempo areas has an architecture that can only be articulated by heeding the composer’s intentions. Specifically, the first movement of Hindemith’s Concert Music for Strings and Brass has two parts–a fast, rhythmic, and melodically intricate opening, and a slow, severe conclusion. Architecturally speaking, you might describe it as a large building with a highly ornamental façade, capped by a majestic dome. The parts are proportionally related, for sure, but the nature of that relationship, the shape of the whole, can only be perceived if the various tempos are correctly chosen.

By equalizing the tempos between the two sections, as Giulini does here, the music’s architectural proportions are ruined: the opening sounds clearly too slow, the second part too fast. The result is insufficient contrast, and monotony. After all, what could be more unsatisfying or ridiculous than a dome the same size as the building below? The entire point of a finely proportioned dome is its verticality, arising naturally out of the massive structure beneath, just as Hindemith’s smoothly flowing unison melody offers a splendidly solemn conclusion to the vigorous first part of the movement. So much for extended analogies: Giulini plays the second movement exactly as written, and it comes off much better. In neither case, however, do the comparatively weak strings balance the power of the brass satisfactorily.

Giulini recorded Dvorák’s Seventh Symphony twice, and neither recording was particularly outstanding (though the first, for EMI, wasn’t bad). Although the Poco adagio here is a good bit swifter than his later versions, he still makes heavy weather out of the first movement, while the scherzo and finale, though well done and considerably more exciting, are simply not distinguished enough either technically or interpretively to give this performance any special claims on the attention of collectors. The same holds true for the Egmont Overture: a typically broad, serious interpretation of no special distinction. If you didn’t know the identity of the conductor, you would not look twice at this disc, particularly given the cavernous and diffuse (though stereo) Royal Festival Hall acoustic.