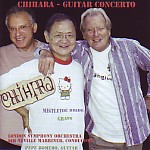

These three works all demonstrate Paul Chihara’s characterful combination of simple melody with cutting-edge orchestral sonorities. He’s particularly fond of atmospheric tone clusters for strings of the kind popularized by Ligeti, and that also feature commonly in horror movies and the like. Indeed, the Guitar Concerto was at least partly inspired by the composer’s love of “scary movies”, and much of it has a certain film noir quality that’s moody and quite captivating. It’s also intelligently scored in such a way that the guitar never gets covered by the orchestra, while the orchestra still makes a significant contribution. The finale offers a few telling moments of a more or less Spanish character, but for the most part the score has little ethnic flavor. It’s just good music, expertly written and extremely well played by Pepe Romero and the LSO under Neville Mariner.

The Mistletoe Bride is a short dance piece written for the San Francisco Ballet, and it has a conceptual affinity to the Guitar Concerto to the extent that it’s a ghost story based on the tale of a young bride married to an older man, taken to live in a large English country house. On her wedding night she begins a game of hide-and-seek and vanishes, only to be discovered years later, a skeleton in a wedding dress. She had locked herself in a closet by accident. This spooky score has plenty of spine-chilling instrumental effects, including a really creepy soprano vocalise (with a touch of insane laughter) and some aptly warped waltz music. It’s great fun, and at just slightly more than 15 minutes it hardly taxes your patience.

Finally, despite many valiant attempts over the years, I have yet to hear a double bass concerto that strikes me as a really distinguished piece of music. As confirmed in various concertos for piccolo, percussion, and other severely limited members of the orchestra, we live in a time where the evolution of technique has outstripped the natural role that these instruments play. The result may be intriguing, but it’s seldom convincing if only because it’s so difficult to create the illusion of a partnership of equals between soloist and orchestra. To this extent, it’s probably better to have two soloists–as here–rather than one, since it multiplies the opportunities for dialog, and Chihara’s concerto has plenty of that scattered among its six brief movements. Certainly the music reveals the same fine ear for sonority exhibited by the other two pieces, and like them, the performances (and sound) are terrific. In sum–this is a worthy and interesting disc, one that fans of good contemporary music will surely enjoy.