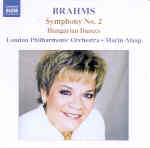

The cover of this disc shows Marin Alsop gazing congenially out at her audience, and the point is clear: this is “her” Brahms. Fair enough. She is more than capable of addressing the music with both respect and intelligence. Unfortunately, though well played and certainly idiomatic up to a point, there is little here that personalizes these performances beyond dozens of other well played, tasteful traversals released over the years. I welcomed the first installment in this cycle as evidence of Alsop’s ability to get a warm, well-balanced sound from the LPO–not your obvious first choice in this repertoire–and for her compelling projection of the score’s grand gestures. But the Second Symphony is not the First. It presents a different, subtler series of challenges, and more to the point, needs to sound different: lighter, less dense in texture, relaxed but never static, and peppered with surprising gusts of passion.

For all of these qualities, the ideal comparison to this newcomer is ready to hand: Eugen Jochum’s cycle with this same orchestra, one of the greatest examples of Brahms conducting available in modern sound. Everything that Jochum does sounds better. He finds the perfect tempo with which to launch the opening movement, and he pays greater attention to those all-important bass lines. Just listen to the first tutti, and hear how he preserves the long arc of melody despite the thick textures. Part of his success also has to do with his sharper approach to rhythm. The syncopations that close the exposition (in both cases repeated) genuinely buoy the soaring, canonic exchanges between high and low strings, while a slight accelerando urges the music onward. It’s exciting, but the music’s essential lyricism is preserved. Alsop sounds heavy in comparison, with a cloudier, less coherent ensemble balance. In the turbulent passages of the development section, Jochum’s more incisive conducting conclusively proves its superiority–and in contrast to Alsop he finds an unusual degree of drama and tension in the Adagio.

Comparing third movements, Jochum takes about a minute longer than Alsop, but he actually sounds swifter, or at all events more eruptive, because he makes so much more of the contrast between slow and fast sections. And in the finale, where Jochum is notably quick, the coda offers a truly satisfying feeling of arrival at a long-awaited goal. The spontaneous release of joy is palpable. Alsop keeps the music tightly reined-in, the brass well in check–and the result has no lift, and little sense of culmination. Mind you, the playing is never less than very good. In some ways the LPO is a finer orchestra than it was in Jochum’s day, but that doesn’t mean “better in this music”. The less blended woodwind textures, those sometimes vinegary oboes, the piercing trumpets that characterized the orchestra in the ’70s, also give the music greater color and personality. In this respect Alsop may not be helped by sonics that do not allow the winds sufficient prominence.

I sometimes wonder if some modern conductors, not just Alsop, have lost the necessary feel for the dialectic of sonata-form typical of Brahms and his school. Jochum had it, of course, and among living conductors Mackerras, Dohnanyi, and Vänskä all seem able to shape the necessary patterns of tension and release, of departure and return, that underpin Brahms’ (and Haydn’s, Mozart’s, and Beethoven’s) particular syntax. What Alsop fails to do is show how the music’s moment-by-moment episodes, however nicely played, lead to its ultimate formal and expressive resolution. Everything sounds in its proper place, but the emotional payoff, the sense of satisfaction that explains why finally getting to the end should matter to us as listeners, is only fitfully present. This isn’t a lack strongly in evidence unless you make real-time comparisons with another, truly great performance, but that is exactly what record collectors have the ability and inclination to do, and so it’s a deficit that many will likely notice immediately.

The coupled Hungarian Dances are also very well-played, and of course don’t require anything like the same kind of effort, expressively or intellectually, that the symphony demands. In limiting herself to those orchestrated by Brahms and Dvorák, Alsop omits No. 5, which frankly diminishes the attraction of the coupling in the first place. Yes, it’s been done to death, but then so has the Second Symphony (at least four new recordings this year alone), and leaving out the most popular item makes no rational sense. But in a way it’s also symptomatic of Alsop’s evident pursuit of a certain abstract ideal of musical purity at the expense of other, more visceral qualities. Brahms was, of course, a musician’s musician, but he also was a human being first and foremost, and it’s the lack of sinew and fiber, of blood and guts, that reveals Alsop as a conductor who has not yet encompassed the full range of what this music expresses.