Britten’s last opera contains some astoundingly beautiful and arresting music: the arrival in Venice, the passage describing the writer Aschenbach’s view of the sea, and of course the haunting, pentatonic percussion music of the boy Tadzio. That said, this opera always has struck me as a comparative failure, in which Britten misses what Thomas Mann himself described as his parodistic, grotesque intent. Attempts to turn this work into a sort of homosexual manifesto also won’t wash. Never comfortable with sexuality of any sort, in his operas Britten either avoided the subject entirely or portrayed it as a corrupting influence, destroying innocence. The attempt to “Greekify” the games of the boys, with Britten’s hooting countertenor and librettist Myfanwy Piper’s stilted language, strikes me simply as distasteful, despite the fact that Aschenbach is punished and suffers death for his “love” at the opera’s end. The cholera epidemic in the second act also falls flat, a mere plot device designed to create urgency in a drama desperately short of it.

Finally, the culminating dream sequence, a rather clichéd battle between the Apollonian and Dionysian conceptions of love, in which Britten confesses (big surprise) that one cannot exist without the other, simply reinforces his own inability to portray any kind of physical attraction, whether heterosexual or homosexual, as normal and natural. However honest and brave it may have been for Britten to lay bare the conflicts within his soul, there is no resolution or satisfaction in doing so: only confusion and resignation. I can well understand why this subject mattered to him, and perhaps to Peter Pears as well, but what Britten has not done is explain clearly in operatic terms why it should also matter to us. This makes the work, to put it mildly, an acquired taste, best experienced by those already familiar with Britten’s other theatrical works and so able to appreciate its characteristic music. And of course, I realize that there will always be listeners who find the conception more sympathetic than I do.

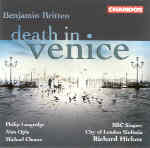

That said, I have nothing but praise for this absolutely terrific performance, in which Philip Langridge offers a vital and intelligent portrait of the tormented Aschenbach, every bit as insightful as Peter Pears’ own, and frankly more appealing of voice. Alan Opie, in his various roles as Aschenbach’s nemesis and tempter, also rivals John Shirley-Quirk on the composer’s Decca recording, while countertenor Michael Chance sounds a touch raw in the “Games of Apollo” sequence–but then, as I said, I dislike the whole scene anyway. Certainly he sounds strange and unearthly, which is the whole point. All of the small parts are very well taken by the individual members of the BBC Singers, and Richard Hickox’s conducting is brilliantly vivid, even sharper and more colorful than Steuart Bedford’s in the Decca permiere. In short, this recording does the composer’s one better, still without managing to make the work a moving dramatic experience, and the engineering is outstandingly clear as well. So if you’re in the market for this problematic piece, or wish to supplement your collection with a second version, don’t hesitate. [5/11/2005]