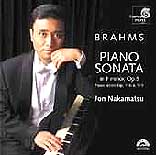

Given his status as a former Van Cliburn International Piano Competition Gold Medal Winner, we should expect more than just technical solidity and dependable professionalism from Jon Nakamatsu’s Brahms. Yet time and again throughout his strong, clearly projected performance of the F minor sonata, you infer missing puzzle pieces. For starters, contrast his matter-of-fact phrasing throughout the sublime Andante espressivo to Emanuel Ax’s lyrical warmth and tender inflection, to say nothing of the same qualities in Arthur Rubinstein’s reference version. Then compare the Scherzo’s jaunty complacency to Earl Wild’s more assertive sweep, or to Arrau’s dynamic heft and emotional intensity. Also notice how Curzon, Kempff, and Freire more urgently shape the first movement’s pedal points. Certainly Nakamatsu’s expertly prepared Finale risks little next to the likes of Katchen, Hough, and Rubinstein. In sum, Nakamatsu’s very good Brahms Op. 5 must compete in the bins alongside many great ones.

The shorter pieces fare better on the whole. I especially like Nakamatsu’s delicate pedaling of the Op. 116 No. 2’s bristling middle section, the bronzed power he brings to the same opus’ concluding Capriccio, and how he takes the Allegro Risoluto marking to heart in Op. 119 No. 4, as opposed to pianists who lay heavily on the block chords. Next to the anguished, otherworldly deliberation of Lars Vogt’s Op. 119 No. 1, Nakamatsu’s faster treatment (more of an Andante than Brahms’ Adagio) makes a less bleak impression. However, a lighter, suppler touch would have been more welcome still in the “Myra Hess” C major Intermezzo (Op. 119 No. 3). Perhaps in time Nakamatsu’s late Brahms interpretations will acquire the linear variety and chamber-like interaction between hands and fingers that distinguish Kempff’s stereo DG recordings and, more recently, Frank Levy’s on Palexa. The sonics have presence and impact, but the piano tone becomes strident and monochrome in louder passages.