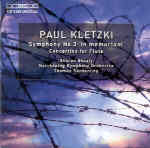

Yes, Paul Kletzki was yet another conductor who also composed (or a composer turned conductor, depending on how you look at it) and the tragic story of his flight from the Nazis and abandonment of his manuscripts makes depressingly familiar reading and surely encourages sympathy as much as it engages our curiosity. But in the harsh light of day the question has to be asked: Just how good a composer was he? On the evidence here, the answer, sadly, is “not very”. The Third Symphony, composed just before the outbreak of World War II, sounds like Honegger on a bad day. The mood varies over a narrow range from grim to grey: I dare you to find the “giocoso” qualification to the scherzo’s basic allegro. Scurrying string fugatos bump up against grinding, “neutron” chords from the brass section, while occasionally a bittersweet tune holds out the frustrating possibility, never realized, of melodic interest. After 45 minutes of relentless angst, most listeners will have had more than enough despite the fact that the idiom as such isn’t really all that advanced or difficult. It’s just uncomfortable and unpleasant without (it seems) being able to justify the investment of effort and time that it demands.

The Flute Concertino is even worse–as dry and characterless a piece as Hindemith in his most “Gebrauchsmusik” manner never wrote. It goes practically without saying that Sharon Bezaly plays the living daylights out of it: her talent and sheer enterprising gamesmanship shines through. So for that matter does Thomas Sanderling’s obvious commitment to the cause, evidenced by the powerful, indeed crushing response he elicits from the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra in the symphony. If this were great music, then Sanderling would be the guy to tell us about it. Certainly I can’t imagine Kletzki being better served either interpretively or sonically, and of course I welcome the opportunity to hear this sample of his work. But I have no desire to repeat the experience, and more likely than not, neither will you.