The violin concertos of György Ligeti and Bela Bartók are two of the greatest works of the 20th century. They are conducted here by the remarkable Peter Eötvös who includes his own violin concerto (2003). As a programming “hook” Eötvös uses the Romanian region of Transylvania, associated with Dracula, but with its large Hungarian population the place where Bartók did his researches into folk music, and where Ligeti and Eötvös were born.

Ligeti’s amazing piece, finalized in 1992, is a compendium of all the styles he had worked in: grotesquerie, folk dance gestures, games with tuning, with glances backward to Medieval and Renaissance sources, and into his own ever-surprising dream world, with a new almost “romantic” feel. There are five movements: the three slow movements have a soaring, almost rhapsodic quality, song-like at first but finally dissolving into despair; the fast movements are dizzyingly ferocious. It is a hypnotic, unforgettable work of remarkable although unique beauty.

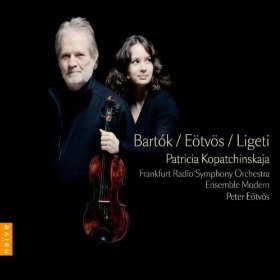

The Ensemble Modern plays for Eötvös as though their lives depended on it. The orchestra accomplishes Ligeti’s extreme demands with sizzling intensity. Similarly, Patricia Kopatchinskaja plays the near-impossible solo part with a biting, unflinching incisiveness, unfazed by the sometimes bizarre effects called for, and etching her way through the soulful material with an aching lyrical intensity. Ligeti left the final cadenza up to the soloist and Kopatchinskaja uses material discarded from the first version of the piece in a very original, slightly crazy way. This performance alone is worth the price of the two CDs.

Bartók’s violin concerto (his second, the first is considered a love-besotted experiment) has become part of the repertory. Eötvös obviously feels it has been taken for granted. He points—some would say overpoints—all the remarkable details in the first movement in ways that risk segmenting the structure. Kopatchinskaja shifts color a great deal, inserts some unusual “gypsy” portamentos, and uses a folk-like freedom in rhythm while suppressing vibrato and adding a tough edge to her tone. There isn’t another performance like this.

The slow-movement variations are given a hard-edged treatment that perhaps too scrupulously avoids the romantic gestures Bartók was starting to use when he composed this work in 1938. When even Pierre Boulez (in his performance with Gil Shaham on DG) sounds glossy in comparison you realize that Eötvös has made quite a statement about the piece.

Speaking of Boulez, he conducted the world premiere of Eötvös’ concerto, which has the sub-title “Seven” (the number dominates the work, the number of movements and the way it is scored) and is dedicated to the seven astronauts who died in the Columbia disaster, who are named in the score, and each of whom is given a “cadenza”. The violinist is called on to execute extremely difficult lines in a declamatory, fierce style. Eötvös evokes the folk music of India and Israel to commemorate the nationalities of two of the astronauts. Occasionally, a more elegiac feel sneaks in, and eventually Eötvös evokes a dream landscape of uncanny timbres and musical lines.

Ligeti is given a great performance; Eötvös is worth knowing. Those coming to the Bartók for the first time may want to look to one of the more agreeable performances, but anyone who knows the piece well will find this an interesting and at times revelatory performance.