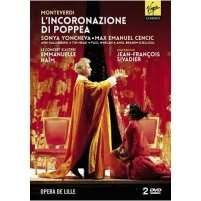

This performance from Lille is directed by Jean-Francois Sivadier, whose Aix-en-Provence production of La traviata starring Natalie Dessay (also on Virgin) caused quite a stir. Though not as radical, Sivadier works with the same idea. The look and feel are almost haphazard: at the start we are back stage, with people milling about seemingly aimlessly, chatting with one another and with the members of the orchestra in gray and brown modern dress. Fortune, Virtue, and Love bicker in front of the others. (The Traviata seemed like a rehearsal; this show has elements of that as well.)

Little by little the players don ancient Roman costumes. We first meet Poppea and Nero in Roman attire as they roll out from under the curtain, held just high enough by the soldiers so they can fit. People who seem extraneous eventually are seen to be characters; props are moved casually and in full view; some of the action takes place in front of the closed curtain. Colors are garish, both for the costumes and the abstract backdrops: the look is “punk”. (Virginie Gervaise is the costumer; Alexandre de Dardel is responsible for the sets.)

The play-within-a-play à la Brecht eventually recedes and the opera turns specifically into itself, up until very near the end, that is. Right after the celebratory music for the coronation and before the final duet, a narrator interrupts and explains what happens historically to Nero, Poppea, and Ottavia. It’s a rude, unnecessary interruption and it breaks the flow of one of opera’s greatest scenes. Oddly, it doesn’t spoil the entire show, but this return to the production’s opening, happenstance/didactic attitude is an imposition. It is also, I presume, Sivadier’s entire point, but it is not Monteverdi’s. The composer tells a sarcastic tale of evil winning over good; Sivadier spoils the fun and breaks the musical flow as well.

It’s particularly odd since Sivadier takes such care in delineating character. His Nero is an insane man/boy whose moods change on a dime and who invariably seems on the verge of hysteria, if not over the edge. Played by the amazing Max-Emanuel Cencic, wearing a mad-looking blond wig rather than flaunting his baldness as he invariably does, this is one dangerous, hyperactive, disheveled Emperor. Cencic sings without transposing the role down and this adds even a bit more frenzy to the top notes, oddly welcome, while the rest of the voice is sensually beautiful and always expressive.

Sivadier plays down the homoeroticism other directors seem to revel in—even in the scene with Lucano—but what it lacks in one sort of sexuality it more than makes up for in another, and the character’s amorality is ferocious. Sivadier paints the normally saintly Ottavia as a woman who, once wronged, turns vicious, cruel, and vindictive, and as a result Anne Hallenberg’s performance is stronger dramatically but less lovely vocally than most. Her harridan-like hair-do makes the point.

Sonya Yoncheva, stunning as Poppea, is almost all determined sensuality, and at times sympathetic to the entreaties of Ottone. Her voice is beautiful in a decidedly non-early-music way—plenty of vibrato (from everyone, actually), and a big, round tone. Countertenor Tim Mead’s Ottone is sung handsomely and acted with sincerity and gravity—he is, in fact, less of a cipher than usual and Mead and Sivadier make us feel for him.

The minor roles are equally well taken. Young Paul Whelan’s bass may not be quite as sepulchral as one likes for the role of Seneca, but it’s a fine sound and his dignity is never in doubt; the backdrop for his death scene is pure white paneling and draperies. His acolytes clearly love and revere him; their pleas to him not to die are heartfelt. After his death he is painted over with white plaster and remains on stage, a ghostly figure watching over the appalling events around him. Amel Brahim-Djelloul is a sincere, loyal, and adoring Drusilla and both nurses are magnificent: Rachid Ben Abdeslam as Nutrice and Emiliano Gonzalez Toro as Arnalta almost walk away with every scene they’re in. And lest I forget, I should also make a point to acknowledge Sivadier’s appreciation of Monteverdi’s (and his librettist’s) humor.

Conductor Emmanuelle Haïm’s choices in scores that allow for leeway invariably seem theatrically and musically wonderful to me, and her way of coloring a scene rarely fails her. There seem to be almost two dozen instrumentalists (the pit is raised but it’s difficult to determine an exact number) who make a grand, joyful, dramatic noise, and the performance is robust and passionate, with tone varying from rounded and loving to slashing and visceral. One appalling decision—up there with Sivadier’s pre-finale narrative—is the use of drums and (what I think is) a thunder machine during some interludes. The sound in these instances is ugly, jarring, and aggressive.

Despite the odd distancing Sivadier works with and Haïm’s strange drum events during pauses, this is an enormously effective Poppea. The David Alden-directed one from Barcelona’s Liceu under Harry Bicket (Opus Arte) is marvelous, though with a mezzo Nero (which I do not prefer, even when it is the spectacular Sarah Connolly); the old Harnoncourt (DG) is cut but sexy, playful, and fascinating (though over-orchestrated), and the Norwegian Opera’s sex-fest and bloodbath version (Euroarts) is not for the faint hearted. Philippe Jaroussky under William Christie on Virgin is magnificent, but Daniele de Niese is a predictable, unsubtle Poppea. This new one, despite its odd, back-door approach, is to be highly recommended.