It’s impossible to know what is in the mind of a composer through the process of writing a piece, but that doesn’t stop people from speculating regarding motivation, intentions, or supposed “meaning” or extra-musical representations in a given work. Dover Quartet cellist Camden Shaw comments on this in his excellent notes to this new release, even admitting to the quartet’s own subjectively applied imagery and how it impacted their “personal response to the [Shostakovich] ”. Yet it’s hard to imagine that, while trying to survive the day to day horrors of a concentration camp (Ullmann, Laks), or experiencing life in a besieged country ravaged by death, depravation, and destruction (Shostakovich) the music that you write wouldn’t be more than a little affected by these circumstances.

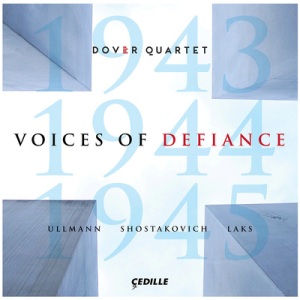

None of the three works here has any declared programmatic intent, but knowing their provenance–Ullmann wrote his quartet while a prisoner in Theresienstadt in 1943; Laks composed his in 1945, after his liberation from years in Auschwitz; Shostakovich’s work came during a stay north of Moscow as war still raged during the summer of 1944–makes it easy to hear within the pages of each, so profoundly and movingly realized by the Dover musicians, more than mere echoes of the myriad, often conflicting emotions arising from the ever-present, inescapable tension and turmoil. Not surprisingly, these include both sadness and longing, but there are also moments in each of these works of beauty and optimism, as well as assertiveness. Whether some or all of these expressive components might add up to something called “defiance”—say, in these works’ more aggressive passages, or perhaps by the simple expression of hope, of serenity in the face of depression, violence, and death—is for each listener to decide.

Viktor Ullmann’s Quartet No. 3 is one of the finest quartets of the 20th century, immediately engaging from those opening seventh chords to the final (defiant?) G major exclamations. Descriptions of the work always include references to Schoenberg (with whom Ullmann studied), and though the influence is discernible (the harmonic freedom; a brief flirtation with a tone row), the style and structure are modeled more traditionally. And while Ullmann plays with tonal ambiguity here and there, the work remains in the tonal world.

Commentators–and even publishers–seem to disagree about the quartet’s organization: four movements? five? or two, as presented in this Dover performance? The Dovers combine the first three sections–Allegro moderato, Presto, Largo–almost without pause, which makes good musical sense; the “second movement” is more like a coda, short, fast, assertive, “mischievous”, darting and dancing until its brief recall of those opening chords.

The Dovers choose to slightly underplay certain dynamics and soften some of the score’s indicated articulations and accents, making contrasts less extreme than they might be (narrowing the range from forte to triple-forte, for instance, in the second movement; the light treatment of cello accents early in the first movement; the barely-there crescendo to forte in the opening measures). But there’s a consistency and balance to the quartet’s approach to this music whose poignancy is still quite real and truly projected. It’s a mystery why this work has received only a handful of recordings; it should be in every quartet’s repertoire, and in every music-lover’s library.

The Shostakovich String Quartet No. 2, on the other hand, has been recorded many times, and quite well, notably by another group on this same Cedille label, the Pacifica Quartet (see reviews). The Dover Quartet adds another exemplary performance, highlighted by the opening and closing minutes of the second movement–entrancing, reflective, serene, yet somehow intriguingly dark. In the third movement a disjointed waltz turns excitingly frenetic–made all the more effective by the Dover’s exacting articulation; the final movement conveys both “tension” and “dread”, just as Shaw describes. It’s a compelling, confident performance–perhaps that “imagery” Shaw and his colleagues imposed on the work really did make a difference!

Yes, we can imagine a “train whistle” at the opening of Szymon Laks’ String Quartet No. 3, as Shaw observes, followed by other allusions to a train ride theme. But you could more easily imagine something more abstract, as the music quickly becomes absorbed in developing Laks’ chosen Polish folk song thematic material. I have to say I wasn’t as enthralled with this work as I anticipated, based on first reading Shaw’s description of the music. Laks has an impressive and very moving story, having survived Auschwitz for more than two years, forced to perform music for his Nazi captors–and for prisoners going to their deaths.

The four-movement quartet stylistically fits very neatly in the company of Ullmann and Shostakovich; much of the musical language is similar (harmonic palette, off-kilter dance rhythms, for instance), yet, although written later than the other two quartets on the program, this work is far more “traditional” in its overall sound and manner. It also struck me as less idiomatic: it doesn’t immediately convince of its string quartet credibility, an essential string quartet nature and character.

Shaw was quite touched by the second movement (“one of the most impassioned and heartbreaking movements for string quartet I’ve ever heard”), and you may be too: it is very beautiful and obviously written from a place of deep reflection and emotion–and the Dovers play it that way. The other movements have moments of brilliance and beauty as well, from the playful, extended pizzicato of the third to the nifty, rich-textured, cleverly varied treatment of the folk melodies in the fourth. (Laks also doesn’t fail to show a bit of a sense of humor–or is it actually something more serious?– displayed in the very endings of the second and last movements.) For me, this piece is a little too long and perhaps guilty of overworking some of its material, but it’s also easy to hear how it would be fun to play, and would make an engrossing concert work.

The Dover Quartet has already demonstrated its deserved place among the world’s premier ensembles, and here, in its exploration and illumination of two lesser-known but also deserving composers and works, rescued from the ashes of mid-20th century Europe, shows a commitment not only to upholding the highest technical and interpretive standards, but to entertain and encourage inquisitive, open-eared audiences. And I should mention that the sound, from the Banff Centre in Alberta, Canada, expertly captures the “feel”, the presence of a string quartet playing live. Here also is another example of imaginative, enlightened–and enlightening–programming. Highly recommended.