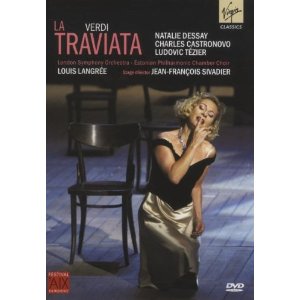

Natalie Dessay remains a phenomenon. She is without a doubt one of today’s great acting singers. She is invariably filled with good ideas that her physicality allows her to execute with great élan, sincerity, and intensity. She never moves like an opera singer; she moves like people move. She does not react a moment before another character sings something dramatically crucial to her; she listens. Vocally, Dessay’s career has had its ups and downs: she was, probably, the greatest high coloratura in the world throughout the ‘90s but began to have difficulties in 2001; in 2002 she required surgery on one of her vocal cords, returned to the stage briefly but required more surgery in 2003. Since her return to the stage in 2005, the voice has been noticeably different: high notes are not as secure (or frequent), the tone can be a bit coarse, and as if to go along with her diminutive physical appearance, the voice often sounds fragile.

In other words, she probably would not be anyone’s first choice as Verdi’s Violetta. You listen carefully to this performance recorded at the 2011 Aix-en-Provence Festival and notice vocal flaws—low notes occasionally disappear into inaudibility; the size of the voice does not allow the “big” moments (“Amami, Alfredo”) to devastate as they should; there is effort in producing high notes. But soon all criticism fades. This turned out to be the most moving reading of Violetta I have ever seen. The wren-like Dessay sickens in front of our eyes; she appears to get smaller and weaker; her third act is high tragedy and almost unbearable.

Director Jean-François Sivadier confuses us somewhat but he can’t get in Dessay’s way. The opera is set in modern day, with the cast dressed casually, except for Alfredo, in white throughout, Violetta dressed-to-party, and Germont in a grey suit. The whole cast is either rehearsing Traviata or taking part in a theater workshop. There’s very little furniture—several chairs get moved around, a blue curtain soon disappears, a few screens with blue sky/clouds and greenery drop in for Act 2, and we are back to a bare stage for the last act. Chorus members wander in and out at will. Alexandre de Dardel is credited as designer. Violetta cues the conductor in Act 1; Flora does the same for her party. The players move well, one and all.

If the purpose is to strip the plot bare, it works—we do in fact get caught up in raw emotions. In other words we utterly stop caring what the metaphor is. Whether or not you like this will be a personal choice; it apparently did not bother me enough, since, as I’ve stated, I was deeply moved by it. But it is deconstructionism at its most thorough—we really have no idea who any of these people are: they exist in a vacuum.

Also as mentioned, Dessay is overwhelming despite the vocal issues and the fact that we’re unaccustomed to hearing such a light Violetta. (Anyone who recalls Toti dal Monte’s recording of Madama Butterfly or Teresa Stratas’ Salome film will understand.) And frankly, there are many, many lovely vocal moments as well: “Ah, fors’e lui”, the duet with Germont, “Addio del passato”—this last a miniature, but deeply affecting. When Dessay removes her party dress and wig at the start of the third act (which begins immediately after Act 2; the opera is presented in two acts, the break coming after the usual Act 2, scene 1), we are looking at a woman who is thoroughly broken. The tragedy is palpable. Argue about the “sound” if you’d like, but there’s no chance that you won’t be touched by her overall performance.

Charles Castronovo’s Alfredo is just right: ardent, embarrassingly young and shy at the start, his tone warm and Italianate. He’s given one verse of “O mio rimorso” and he caps it with a fine high-C. He somewhat lacks vocal charisma, but this is merely an observation: not everyone has to be a star. And whoever Violetta may be in this production, she seems to adore her Alfredo. Ludovic Tézier’s Germont Père is handsomely sung, with long lines and grand tone, but he doesn’t command the stage. Is this director Sivadier’s doing or is it Tézier’s? He too gets a verse of his cabaletta.

Louis Langrée’s conducting is controversial; it’s almost too classical. True, he builds the final act’s tension nicely, but for most of the performance, despite beautiful playing and singing from orchestra and chorus, it seems a bit too well-mannered and manicured, leaving Dessay (and Verdi) to create the tension and drama.

Both sound and picture are superb. Virgin’s presentation is paltry: a four-page insert with pictures of the production and the names of everyone involved. No extra material. I don’t think I can recommend this as a first Traviata—in some ways, it isn’t quite a “Traviata” at all—but it will take your breath away. Of course, so does the Netrebko/Villazon from Salzburg, and many (not I) salute Renée Fleming in the role (I find her as spontaneous as a Broadway show), and the Stratas/Zeffirelli film is sui generis. Over to you—but this is really one for the books.