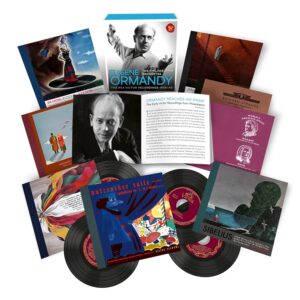

Eugene Ormandy’s 78 RPM output with the Philadelphia Orchestra for RCA Victor may seem like a drop in the bucket compared to his immense Columbia Masterworks discography contained in Sony BMG’s three mega box sets. Yet hearing these newly remastered recordings reveals that the Ormandy/Philadelphia partnership’s salient virtues were well in place during the conductor’s first years as the orchestra’s co-director and (starting in 1938) full music director. These include equally balanced orchestral strands, opulent string tone and impeccable ensemble precision, not to mention being the best accompanist in the business on the podium. While the original sound quality of these sessions varies from grungy to surprisingly robust for the period, Sony BMG’s restorations are as good as one will get, barring the additional spaciousness and amplitude heard in Mark Obert-Thorn’s relatively interventionist transfers for Andrew Rose’s Pristine Audio label. Here is a disc-by-disc description of the contents.

CD 1: The largely forgotten American violin virtuoso Albert Spalding’s Mendelssohn Concerto is rather “plain Jane” when measured alongside rival 78 RPM versions by Milstein and Heifetz, but his supple technique and warm tone truly shine in the Spohr Concerto No. 8 in A Minor. Fritz Kreisler was still on good form for a 1936 recording of his liberally recomposed Paganini Concerto No. 1, although he’s a bit backward in the mix.

CD 2: The sluggish and heavy Beethoven Symphony No. 1 pales beside the better known Toscanini/BBC recording from the same period; for some reason the fourth movement is pitched ever-so-slightly flatter than the three earlier movements. By contrast, the orchestra is on splendidly responsive form in the Schumann Symphony No. 2; note the whiplash string runs and powerful horns in the Finale, as well as the euphonious woodwinds in the Scherzo’s trio.

CD 3: The 1936 Tchaikovsky “Pathetique” was Ormandy’s first of many recordings of this work, and possibly the most incisive and texturally transparent of them all, as borne out in the unusually fine engineering for its time. Those who know Ormandy’s incomparable Columbia stereo Nutcracker suite will discover comparable mastery in the conductor’s 1941 recording, which I find superior in nearly every way to the 1945 remake (compare the crisp 1941 Overture to its sluggish 1945 counterpart, for example).

CD 4: For his first recording of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Ormandy commissioned Philadelphia clarinetist and “house arranger” Lucien Cailliet to orchestrate the work. Whether or not it was intended as an “answer” to the Ravel version commissioned by Koussevitzky, Cailliet’s instrumentation is more conventional and less impactful, with a greater reliance on strings. Cailliet assigns “The Old Castle” theme to the English Horn, in contrast to Ravel’s saxophone, while Schmuyle all but disappears when played on the oboe, unlike Ravel’s hectoring muted trumpet. However, Cailliet includes the Promenade before “Limoges” that Ravel omits. While Liszt’s Les Preludes is cleanly played, it lacks the gravitas and grandeur of Ormandy’s late 1940s Columbia 78s and his stunning stereo 1960s remake. The 1941 Enescu Roumanian Rhapsody No. 1 is certainly well played, yet lacks the idiomatic swagger and characterful edge of Ormandy’s 1934 Minneapolis recording. The Philadelphians, however, play Charles O’Connell’s effective orchestration of Debussy’s Minstrels to the hilt.

CD 5: Basically soprano Kirsten Flagstad’s greatest hits from her prime, with Ormandy’s support in Beethoven’s Ah! perfido and Abscheulicher!, Weber’s Ozean, selections from Wagner’s Die Walküre and Lohengrin, plus the Immolation Scene from Wagner’s Gotterdämmerung. Wagner sniglets with Hans Lange beating time fill out the disc, along with three gorgeous tracks featuring soprano Dorothy Maynor.

CD 6: Tenor Lauritz Melchior’s greatest Wagnerian hits, albeit somewhat past his prime, mostly led by Ormandy, with Edwin McArthur sort of beating time on four selections.

CD 7: Unusually well engineered for its day, Ormandy’s 1938 world premier recording of Strauss’ Sinfonia Domestica is a tour-de-force of stunning orchestral virtuosity, not to mention the supple and sophisticated textural interplay Ormandy elicits throughout. None of the subsequent 78 RPM and mono LP versions came close to Ormandy’s musical and technical standards, not even the “fabled” 1945 Bruno Walter/New York Philharmonic broadcast. And those string portamentos in the Rosenkavalier Suite: sumptuous but never vulgar.

CD 8: The American composer Harl McDonald (1899-1955) was the Philadelphia Orchestra’s manager from 1939 until his death. His style is less identifiably American than French or Slavic; indeed, the central movement of his Santa Fe Trail Symphony owes its existence to “Fêtes” from Debussy’s Nocturnes. Two of McDonald’s Three Poems on Aramaic themes could well have been written by Glazunov. Though no memorable tunesmith, McDonald’s strong harmonic imagination and ingenuous orchestration play to the Ormandy/Philadelphia partnership’s strengths.

CD 9: Here we have Caillet’s lush arrangements of Vivaldi’s Concerto for 2 Violins, Strings and Basso continuo, a suite from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and Jenkins’ 5-Part Fantasy, along with big-band (that is, pre-period instrument) performances of Mozart’s Divertimento for 2 Horns and Strings K. 247 and Telemann’s A Minor Suite TWV 55:a2. Call this style of playing old fashioned, yet Ormandy’s fervent musicality unquestionably comes across.

CD 10 and 11: Rachmaninov at the piano in his First, Third and Fourth Concertos. The great composer/pianist is on his most authoritative form in the First Concerto’s opening movement, capped by a pulverizing cadenza. At the risk of heresy, I prefer more interpretively electrifying and sonically superior versions of the Fourth Concerto by Michelangeli, Wild and Biret to the composer’s. Although I like Rachmaninov’s fast outer movement tempos in his Third Concerto performance, he sounds perfunctory next to Horowitz. He also makes many cuts, and it’s worth pinpointing them here. In the first movement, we lose three bars after rehearsal number 10 up through rehearsal No. 11. In the second movement, the music is cut from six bars after No. 27 to eight bars after No. 28. The two third movement cuts are from No. 45 to nine bars after No. 46, and then two bars after No. 52 to No. 54. Arthur Rubinstein’s first Grieg Concerto recording fills out CD 11, and it remains the freshest and most vibrant of the four he would eventually make.

CD 12: The Brahms Double Concerto with Jascha Heifetz and cellist Emanuel Feuermann coupled with Feuermann as protagonist in Strauss’ Don Quixote: need I say more? These were the 78 RPM reference versions, and they’re still fabulous.

CD 13: Power and poetry always informed Ormandy’s way with Brahms’ Second Symphony, and his 1940 Victor recording easily stood its ground in the 78 RPM catalog alongside the Barbirolli and Rodzinski New York Philharmonic versions and the first Monteux/San Francisco traversal. Marian Anderson is in better voice for her Ormandy-led Brahms Alto Rhapsody than in her San Francisco remake with Monteux, and her majestic contralto still sends shivers in a further group of Brahms songs filling out the disc.

CD 14: Ormandy’s 1939 Strauss Ein Heldenleben received mixed reviews at the time of its release, with several critics comparing him unfavorably alongside the 1928 Mengelberg/New York Philharmonic recording. I can understand why: The Hero’s Adversaries droops along, while Ormandy skates through The Battle as if it was an amphetamine ballet. I prefer the more judicious pacing, tempo relations and transitions distinguishing Ormandy’s 1954 Columbia mono remake. The surface sheen and high octane energy of Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloe Suite No. 2 from 1939 also delivers a knockout punch, although the airier, more balletic Koussevitzky/Boston 1945 recording would eventually supercede it in the Victor catalog.

CD 15: All Sibelius: the 78 RPM era’s hottest and best played Finlandia, Lemminkänen’s Return and First Symphony. Ormandy would tinker more with the symphony’s percussion and harp parts in his Columbia stereo version.

CD 16: Ormandy played more contemporary music than he’s usually given credit for. His 1942 Hindemith Mathis de Maler Symphony leaves the earlier composer-led Berlin recording at the starting gate. The ink had barely dried on the page when Ormandy made these first-rate recordings of Menotti’s Amelia Goes to the Ball Overture, Barber’s First Essay, and Roy Harris’ Three Pieces for Orchestra. It also sounds as if the musicians were thoroughly enjoying themselves while recording Sousa’s Washington Post March and Stars and Stripes Forever .

CD 17: Four Bach/Cailliet transcriptions – these are less garish than Bach/Stokowski, yet equally sumptuous. Ormandy conducts three of them, while Stoki takes over for the E Major Violin Partita Prelude transcription. Three Strauss Waltzes (Voices of Spring, Vienna Blodd and the Emperor Waltz) go as well as you’d expect from these forces.

CD 18: See my earlier comments about the 1945 Tchaikovsky Nutcracker Suite. However, had Toscanini ever chosen to conduct the Tchaikovsky Fifth Symphony, it may well have sounded like the first of Ormandy’s five commercial versions. Listen to the first movement’s lean and snarling textural strands and galvanizing climaxes, and you’ll get what I mean. It should be said that Ormandy’s 1945 recording presented the score without the various cuts found in other 78 RPM versions by Stokowski, Stock, Rodzinski and Mengelberg.

CDs 19, 20 & 21: Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra recorded several items anonymously in 1938 and 1939 that were released in a “World’s Greatest Music” series of albums credited to the “NY Post-Symphony Orchestra. Good, solid and not particularly special performances of the Beethoven Fifth, Schubert Eighth and Mozart 40th Symphonies, along with equally decent yet unmemorable Bach Brandenburg Concertos Two and Three. The Brahms Second Symphony is less well recorded and played than the aforementioned 1940 recording.

A 71-page booklet contains excellent notes by Richard Evidon and thorough session documentation. Kudos to Robert Russ and his production crew for once again restoring Ormandy’s recorded legacy in the right way. Now will Sony/BMG will be able to work sonic miracles on Ormandy’s complete stereo RCA output?