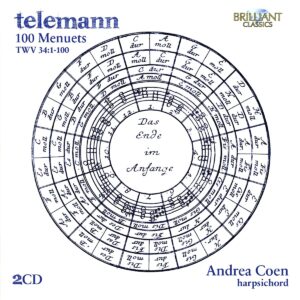

Telemann composed two collections of short pieces titled “Seven times seven plus one Menuet”. Goodness knows what that means, but the reality is that the pieces add up to 100 menuets. They range from 16 to 40 measures apiece, with phrases parsed out in four measure groups.

Telemann arranges the Menuets in upward progressions by key, alternating between major and minor mode. For example, Menuets 1 through 7 are either in A minor or A major, numbers 8 through 11 are in B-flat major, 12 through 14 are in B minor, 16 through 20 alternate between C major and C minor, followed by number 21 in C major. You get the picture.

Harpsichordist Andrea Coen plays the Menuets in more-or-less the same brisk tempo, one right after the other. That’s two and a half hours of continuous music, the baroque equivalent of a DJ spinning out consecutive, similarly paced songs. What is more, Coen tends to shoehorn embellishments and expressive gestures within the beat. Coen doesn’t do so with unyielding rigidity, to be sure, yet he certainly doesn’t stop to smell the roses. He’s more of an urgent than a poetic type of player. In this sense, Coen seems to approach his Telemann marathon as performance art, a manifesto, or an existential act. Imagine if Satie’s Vexations or 100 Bottles of Beer had Telemann’s tuneful variety, and you’ll get the idea.

If I were to play all 100 Telemann Menuets in a single bound, I’d aim for contrasts in tempo, mood, dynamics, voicing, pacing, and so forth. I’d think, “what kind of an eventful artistic journey could I forge from such modest and formally repetitive material?” Until that day arrives, Andrea Coen’s one-tempo-fits-all Telemann Menuets is our only option. But at least you can dance to it.