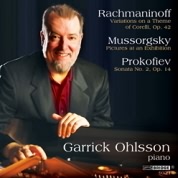

While others may bring more panache and kinetic sweep to the Rachmaninov Corelli Variations and Prokofiev Second sonata than Garrick Ohlsson, his rhythmic discipline, strong harmonic awareness, and astute ear for tone color pay insightful musical dividends. In the Rachmaninov, for example, the first two variations’ Bach-like thread effortlessly dovetails into Variation 3’s wry humor. Ohlsson’s seemingly plodding pace for Variation 5 actually provides a base from which the following two variations can build. The only time when Ohlsson’s architectural awareness slips into static languor occurs in the lyrical Variations 15 through 17.

Although Ohlsson takes the Prokofiev Sonata’s second and fourth movements relatively slowly, his measured pace allows more dramatic differentiation between marcato and legato passages. The austere slow movement often comes across as no more than melody and chordal accompaniment, but Ohlsson pays heed to the keyboard writing’s inner voices, and duly gauges the climaxes in linear terms.

Lastly, an unbridled, big-boned 1974 live performance of Pictures at an Exhibition captures a younger, more impetuous Ohlsson on top form. The sonorous climaxes of Bydlo, the Market Place at Limoges, and the final two movements make a forceful impact without the least splintering or banging. By contrast, Tuileries and the Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks are light, supple, and curvaceous. Furthermore, the Czech Radio archival recording captures Ohlsson’s huge, singing tone with flattering concert-hall realism. Although there’s much to savor from the 60-something Ohlsson’s Rachmaninov and Prokofiev, the young whippersnapper’s Mussorgsky ultimately steals the show.