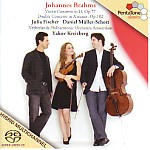

The Violin Concerto is arguably Brahms’ finest work in the concerto medium. He was always at his best when facing a serious musical challenge, in this case pitting the solo violin against the full orchestra. The very nature of the task played to Brahms’ strengths, permitting him to create a work whose symphonic integrity is matched by the beauty of its themes and the mastery of their scoring. This may seem obvious, and heaven knows the work needs no recommendation from me, but it’s worth mentioning all the same because the best performances understand and project those special qualities that make the concerto such a remarkably integrated whole, a true partnership of equals. This technically superb performance comes close, as so many modern performances do, but doesn’t quite capture the expressive essence of the music in the way that, say, Oistrakh, Heifetz, Milstein, or Szigeti did at various times.

As is so often the case, the biggest problems arise in the first movement. At just a bit more than 23 minutes, it’s too slow (tellingly, Oistrakh/Klemperer is quicker). This is less a function of absolute tempo than of contrast between the quick music and the more lyrical or reflective passages, where tension tends to sag, and where Fischer’s tone (for all its basic sweetness of timbre and excellent intonation) can turn comparatively thin. The problem is exacerbated by conductor Yakov Kreizberg, who sculpts an introduction on the grandest scale, with huge contrasts of tempo and dynamics. It’s not surprising that Fischer isn’t quite up to the challenge that Kreizberg presents. Her response is clean, spirited, and technically impeccable, but it needs to be heroic. Though nearly impossible to quantify in words, there’s a certain bigness of character, an element of risk, that’s audibly missing.

This is much less of a problem in the slow movement and finale, both of which are just about spot-on. The former opens with a nicely phrased oboe solo and continues with Fischer highly responsive to the opportunities for lyrical dialog with the orchestra. The absence of any need to adopt a confrontational musical persona allows her to let her instrument sing feely, and very expressively. In the finale, both Fischer and Kreizberg go for broke, adopting a very swift basic tempo and bringing as much energy and fire to the music as anyone. Once again, the fact that both solo and orchestra find themselves operating in tandem most of the way makes the performance much more successful than in the first movement.

The Double Concerto has a major asset in the person of cellist Daniel Müller-Schott, an excellent performer who guarantees that, unlike so many versions of this work, neither of the two soloists dominates at the expense of the other. That said, and despite this being a more emotionally restrained work than the Violin Concerto overall, you will hear the same combination of technical polish and slight want of character as previously. Frankly, I hate writing impressionistic criticism like this. I want to be able to say “at figure x such-and-such clearly goes especially right or wrong.” Nothing like that happens here: Kreizberg and the orchestra are in fine form, the first movement (in this case) is taut and well-argued, the slow movement lovely, the finale smashing. But in the final analysis, it’s just not as moving or memorable as it should be. Admittedly, this is highly subjective, but there it is.

It’s interesting to reflect a bit on this release, coming as it does hard on the heels of Fischer’s wonderful Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto. That piece offers none of the intellectual challenges of the Brahms, with sheer virtuosity constituting a good deal of the music’s expressive point. It may be that Fischer still needs a bit more experience, and a stronger personality profile, before tackling Brahms (and Beethoven). Recordings today seldom represent the mature reflection of a seasoned artist; they are calling cards useful in getting live concert engagements. Fischer is a hot commodity at present not because of her artistic insight and wisdom, but because of her youth and novelty. This doesn’t mean that Fischer’s efforts here are not sincere, or that she isn’t tremendously talented. She is both. But she also may be doing too much, too fast. PentaTone needs to slow down. The last thing I want to see in 20 years is an interview with Fischer on the occasion of the release of her next recording of the Brahms concerto, in which she admits (as she surely will) that she wasn’t yet ready when she made this one.