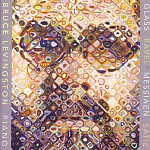

The concept of musical piano portraits based upon or inspired by specific people or subjects purportedly unites the works Bruce Levingston assembles for this recital. Whether or not Philip Glass’ two-movement portrait of his friend, painter Chuck Close, mirrors the latter’s visual style in musical terms shouldn’t influence your direct response to the composition; it turns out to be one of Glass’ most beautiful piano pieces. His trademark repeated ostinatos, scales, and strategically deployed single notes veer off into unpredictable harmonic juxtapositions and polyrhythmic combinations that sit as comfortably as a fun-house mirror. Although Glass’ writing often seems built out of modular blocks (musical Lego sets, perhaps), he has an unerring sense of just how long each module should be, as well as how to mete out harmonic density in the right proportions. What is more, Levingston’s solid rhythmic sense and astute textural control makes the music seem easier to play than it actually is.

The Messiaen selections, of course, require transcendent virtuosity and a huge arsenal of tone color, which Levingston has. I especially warm to Levingston’s Satie, where he creates an illusion of the melody lines and accompaniments stemming from different instruments. Yet I wish he had brought similar tonal allure to Ravel’s La vallée des cloches. In the same composer’s Alborada del gracioso, Levingston doesn’t quite match the assurance and razor-sharp articulation that others bring to the notorious repeated notes and vivacious rhythmic patterns. Incidentally, Levingston’s sonority is fuller-bodied and more dynamically varied in real life than the drab, slightly constricted engineering suggests.