Hieyon Choi has been performing Beethoven’s piano sonatas for decades, with several complete cycles to her credit in various concert venues. Between 2015 and 2023 she committed all 32 sonatas to disc in Berlin’s Teldex studio on a beautifully regulated Bösendorfer grand. The instrument’s timbral distinctions between registers and mellow colors may not convey the power and projection one finds in the best Steinways, yet they somehow suit Choi’s consistent attention to small details of articulation and voicing over the course of her interpretations.

She’s especially persuasive in the early sonatas. Her Op. 2 No. 1 Allegro may lack the unbuttoned fantasy of Schnabel, Pollini and Kovacevich, yet her contrapuntal awareness and strong left hand presence compensate, as do the finale’s hair-trigger precision. Op. 2 No. 2 is a model of lightness and witty inflection, while Op. 2 No. 3’s finale fuses scurrying brio and harmonic tension. In Op. 10 No. 1’s finale, Choi takes Beethoven’s optimistic Prestissimo directive at his word, while her sophisticated scaling of dynamics and pinpointed timing of chords and silences left me awestruck: this is one of Op. 10 No. 1’s greatest recorded performances. Op. 10 No. 3’s outer movements have similar effortlessness and specificity of detail, although one misses the breadth and timeless aura that others bring to the Largo, like Arrau, Hungerford, and Horowitz.

Choi’s “Pathetique” Sonata features an unusually pliable Adagio cantabile bracketed between rather cautious outer movements, while her Op 14 Sonatas are eloquently nimble. She captures much of Schnabel’s zaniness in Op. 27 No. 2’s Allegro molto, but the “Moonlight” (Op. 27 No. 2) suffers from too many studied tenutos, a mincingly arch Allegretto and a Finale lacking in vehemence. Low voltage performances of Op. 28 and Op. 31 Nos. 1 & 2 contrast to Op. 31 No. 3’s textural transparency and crystalline accentuation. The “Waldstein” comes of as poised and professionally groomed as one would expect in a modern-day recording, yet urgency and dynamism only appear after the Rondo gets going. If the “Appassionata’s” subito dynamics don’t shock and sting a la Rudolf Serkin or Sviatoslav Richter, Choi’s concentration and control are never in doubt. She especially shines in the Allegro ma non troppo, creating a cumulative momentum that peaks with a borderline breakneck coda that never derails into pounding or hysteria.

The pianist’s lumpy and foursquare Op. 78 first movement barely hints at the characterful humor and playfulness she brings to the Allegro vivace. She crosses every “t” and dots every “I” in “Les Adieux,” yet the overly sectionalized results put pianistic effect on the proverbial front burner. It’s hard for me to determine if Choi’s outsized dynamics and grand rhetorical gestures in Op. 90’s first movement either are mannered or highly personalized. Also note her gripping pianissimos in Op. 101’s opening Allegretto, and her dead of center accuracy in the second movement March’s treacherous skips. For all of Choi’s admirable solidity and meticulous finger work throughout the “Hammerklavier,” the interpretation is a tad studio-bound in regard to the pianist’s conservative tempos, undermined climaxes and lack of abandon when the music really needs it (the Scherzo’s wacky upward scales, the Fugue’s build-up right before the quiet D Major section).

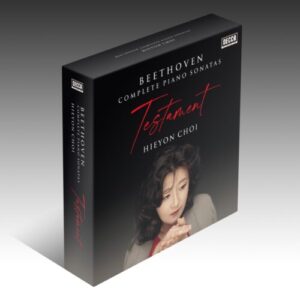

Choi’s Op. 109 is preplanned to a fault. At the risk of overusing the word “sectionalized,” this is exactly how her third movement variations unfold, more as individual display pieces than unified components that flow in and out of each other. On the other hand, the pianist’s bracing Prestissimo takes Beethoven’s legato and detaché phrasings into account, whereas many pianists don’t bother to do so. But Op. 110 receives a heartfelt, intelligently proportioned and fully internalized interpretation. The grandeur of Choi’s Op. 111 introduction assiduously leads into a powerful, superbly controlled and markedly contrasted first movement main section. Listeners acclimatized to spacious, otherworldly Ariettas (Schnabel, Arrau, Pogorelich) may take issue with Choi’s fast pace and stringently held tempo relationships; like it or not, the pianist realizes her conception successfully. Whatever individual reservations I harbor over certain items, Hieyon Choi’s Beethoven certainly has much to offer, and I know that I’ll return to many of her performances with pleasure, especially in the early sonatas. While this cycle’s physical edition is hard to source outside of South Korea, it is readily available via major download and streaming services.