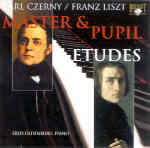

Like most didactic piano etudes, Carl Czerny’s The Art of Finger Dexterity Op. 740 holds negligible musical interest. Still, it’s good that budding piano students (and perhaps a few technique groupies) can hear them played to world-class standards here. Not only does Fred Oldenburg easily command the cruelly exposed double notes, arpeggios, lightning-quick passagework, and all other hurdles Czerny throws at him, but he also executes these patterns with the utmost in rhythmic verve and musicality. What’s more, Czerny’s optimistic tempo preferences do not faze this pianist, who clearly revels in the sparkling clarity of his Yamaha concert grand.

But the more substantial musical demands of Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes do not show Oldenburg to his best advantage. Part of the problem lies with his choice of instrument, an 1842 Erard. It simply lacks the resonance, sustaining power, and dynamic projection this music needs and the best modern instruments supply. As a result, the first etude’s bass-register trills sound gingerly rather than majestic, while the long, lyrical lines in Paysage and Ricordanza fall short of breath. The balance of power between melody and accompaniment often loses focus in Oldenburg’s hands. His clattery, flustered account of Mazeppa is an example, while No. 10’s busy triplet accompaniment overshadows the melodic line, and Chasse-neige’s tremolos create a dominating, silent-movie effect. However, Oldenburg turns in a fleet and relaxed Feux Follets, a galvanic Wilde Jagd, and an incisive, well-articulated A minor etude. This is recommended for the Czerny, although it’s best to listen to this kind of music in small doses. For the Liszt, Arrau still dominates modern recordings, not to mention the essential mono Cziffra and Berman editions.