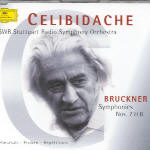

Sergiu Celibidache felt a particular spiritual affinity with the symphonies of Anton Bruckner. They constituted the core of his repertoire, and he had very strong opinions about their performance, referring to other “so-called Bruckner conductors” as “camel drivers” who “haven’t understood the first thing about Bruckner.” Whatever one thinks of Celibidache’s rhetoric, these live 1970’s performances, part of Deutsche Grammophon’s Celibidache Edition, allow us to hear how this famously elusive conductor (he hated recordings) actually played Bruckner. Celibidache protested that recordings were “not music”, and philosophically, at least, he had a point. There are innumerable phenomena taking place during a performance that are not captured by sound recording devices. Perhaps it’s these missing intangible aspects that bar these performances from the realm of the extraordinary. Because, despite all the legend and hype, what we have here is some pretty much standard Bruckner, recorded in not very good sound. By comparison, the later EMI recordings with the Munich Philharmonic (in first-class sound) feature readings that, with their amazingly slow tempos and shockingly sustained intensity of orchestral playing over the long time-spans, better represent Celibidache’s musico-mystic image.

Symphony No. 7 runs a little over an hour on the DG set, and except for some added timpani rolls in the adagio’s climax, comes off as pretty straightforward. The Stuttgart Eighth sounds rushed compared to the Munich performance, which clocked in at over 100 minutes. Only the finale’s unusually broad pacing hints at the incredible expansion that was to come. Celibidache’s Stuttgart Ninth, the freshest, most direct performance of the three, moves along in a very brisk manner which comes as a shock after his big, heavy and very long EMI account. Okay, so what’s so special about this DG set? Perhaps the answer lies in Celibidache’s concept of orchestral sound itself. Unlike his last years, during which he strove for ultimate clarity of inner detail and musical line, Celibidache’s earlier Stuttgart style aims at just the opposite– heavily blended sonorities, smoothed accents and rounded attacks–mannerisms that may have sounded transcendental in performance, but which in these dynamically limited and recessed recordings make the music sound soft-edged and underplayed. At least the EMI recordings present a Bruckner experience you won’t hear anywhere else (whether or not you’ll want to hear it very often remains an open question). Barring those, and unless you really want the coupled Schubert Symphony No. 5 (a fine reading) or the bonus disc of Celibidache painstakingly rehearsing the same few minutes of the Seventh and Eighth symphonies over and over (in German), go for Eugen Jochum’s contemporaneous and far more idiomatic performances with the Dresden Staatskapelle on EMI.