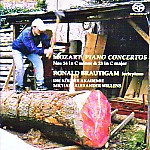

The cover of this CD, a lumberjack hacking at a huge log with an axe, is delightful. Replace the log with a twig, keep the axe, and you have the perfect visual analog to the playing of Die Kölner Akademie’s string section. After reviewing the last installment in this evidently ongoing series, I received the following note from conductor Michael Willens: “Since you are clearly completely unimpressed with what we do, it might make more sense for you to jerk off at home rather then [sic] in public. I am sure that the classical music community and CD buying public will be most thankful.” No doubt Mr. Willens, who was responding not just to that review but also to my comments about his mediocre Kalliwoda disc on CPO, will find readers who agree with him, which is one reason why I bother to share his rejoinder here. The other reason, the one he seems unable to fathom, is that my job is to alert listeners to dreck masquerading as music, and a good bit of the CD buying public is “most thankful” for that as well. Besides, there is no such thing as bad publicity, even when it comes in the form of a “dreck alert.”

The problems with this release are basically the same as those with the last one, only more so. Willens has at his disposal a pint-sized period-performance pickup band, with a teeny, tiny string section playing with the kind of desiccated “authentic” tone that would have made Mozart roll over in his grave, and that makes hash out of his carefully calibrated orchestral textures. The harmonic filler is often louder than the tunes, with the curious result that even with such small forces tutti passages tend to sound clogged. Bass lines also have less impact than they should.

These concertos, particularly with their large wind sections (including trumpets and drums), come across as sounding like asthmatic wind serenades accompanied now and then by anorexic violins. The wind parts, breathy and noisily played, are consistently too loud. They hardly ever achieve a true piano dynamic. At the same time, the trumpets (not the timpani) turn timid in the fortes–just check out the opening of Concerto No. 25. Mozart wants grandeur; what he gets here is desperation.

The result is emotionally sterile. The opening of Concerto No. 24 has no feeling of menace or pathos. Phrasing is clipped and choppy. Brautigam and Willens race through the central Larghetto for the simple reason that the chosen fortepiano has no sustaining power to its tone at all, and the orchestra sounds like hell whenever it needs to hold a note longer than a fraction of a second. Indeed, Brautigam’s instrument is a bit of a joke. When I was in high school there was an old grand piano in the student lounge, and we used to amuse ourselves by placing empty aluminum soda cans on the strings to generate a tinny, saloon-like twang–sort of a cross between a harpsichord and a tack-piano. Well, that’s what we have here.

It may seem from the foregoing that I am opposed to “historically informed” performances. Not true. I am opposed to ugly performances. There are wonderful interpretations of this music that adopt essentially the same approach, most recently for example by Alfred Brendel with Charles Mackerras (Philips). Or consider Bilson/Gardiner, incomparably more stylish and dynamic than what we have here. There are also beautiful examples of 18th-century fortepianos: this is not one of them.

You may think that I found Willens’ comment to me offensive. I did not. He was upset. He is entitled to his anger, and to direct it to the source. But what does bother me is the notion that only those who are impressed with his work have the right to speak about it in the first place. That is delusional. So too is the implication that his intrepid but outclassed band withstands comparison to the finest orchestras and ensembles that have already set down this music on disc. If you want to play in the big leagues, then you have to be prepared to take a pounding now and then. You can either get better and become competitive, or you can sulk as you return to the obscurity from which you emerged. As to Brautigam, I have championed his recordings for years: he is a bold, exciting, and often intriguing pianist; but on evidence here, he is not a Mozart player of any special distinction, and he’s made some bad choices. Music lovers deserve better.