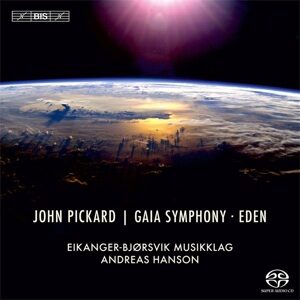

Writing a 65-minute piece for band (and extended percussion) presents no small challenge, one that John Pickard has approached thoughtfully, if perhaps not entirely successfully. The four movements of his Fourth Symphony (“Gaia Symphony”) are subtitled: Tsunami, Wildfire, Aurora, and Men of Stone, the latter itself a sort of “four seasons” suite. Between them come three “windows” scored for percussion alone that serve as transitions between the movements. Starting with the “windows”, the composer notes that he felt it helpful to give the brass players a rest between the often insanely virtuosic larger movements, and doubtless they will thank him for his consideration. But are these pieces, motivated as they are by extra-musical considerations, and that sound rather like generic modern percussion writing, musically necessary? I’m not so sure.

Then there is the style and sequence of the movements themselves. Pickard scores for band with confidence, and achieves some amazing textural effects, especially through the use of rapid figurations on the trumpets at lower dynamic levels. He manages to create lengthy passages of sustained sonorities such that you would never know that he has restricted himself to wind instruments. That is quite an achievement. However, especially at climaxes, the timbre of the brass can be fatiguing, particularly when punctuated, as here, by the regular bashing and crashing on various drums. And if I hear one more modern work where almost every crescendo is accompanied by a Hollywood-esque roll on suspended cymbals, I will immediately add the disc in question to my collection of coasters.

That said, the real problem occurs in the finale, “Men of Stone”. Musically programmatic nature pieces, such as we find in the first three movements, can get along splendidly as studies in rhythm and texture, but the obvious (and really only intelligible) thing to do once “Man” shows up is to write a distinctly vocal tune. Pickard, to his credit, seems to be aware of this: at this point the music turns optimistically tonal and it does become more melodic, but to my mind he doesn’t go far enough, perhaps because of the finale’s need to mind its own musical business as (originally) an independent work. More significantly, coming after so much Sturm und Drang “extended tonality”, the harmonies of the bright conclusion sound more than a little bit corny–a result a good melody might have ameliorated. None of this is to deny Pickard’s genuine achievement in writing a very extended, often captivating work that does try very hard to sustain the listener’s interest throughout its length.

Gaia’s discmate, Eden, is a 15-minute test piece for band in simple ABA form, with the outer sections evocative of calm tranquility and a central episode of great violence and excitement, obviously representing inimical forces. Pickard suggests that those are us, but again, there’s nothing special in the noise and commotion to convey that unambiguously, and to be honest it doesn’t matter. Music is, in general, perfectly helpless to point a moral with that kind of specificity, but it can illustrate paradise despoiled with the convincing gusto that Pickard offers here.

Whatever one’s view of the music itself, the performances by the Eikanger-Bjorsvik Musikklag under Andreas Hanson are utterly brilliant–superbly played in all departments, and stunningly well recorded in SACD multi-channel sonics by BIS’ engineers. This is, all in all, an enjoyable and challenging disc, and the question of whether the composer’s ambition has exceeded his grasp can only be answered on an individual basis–over the short term–and by the winnowing process of time thereafter. At least we have the chance to listen and judge.