Verdi composed I masnadieri, based on a play by Schiller, for Her Majesty’s Theatre, the Haymarket, in London. It was premiered in 1847 and was his first non-Italian commission—an honor that had not been bestowed on his three great predecessors, Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti. It was his sixth opera in four years, appearing just four months after Macbeth. The opera starred Jenny Lind, known as “The Swedish Nightingale”, probably the most famous soprano in the world at the time, in the opera’s only female role. Verdi did not compose cadenzas for her two arias—she was known to devise her own—and the opera was well received, with Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and the Duke of Wellington in attendance.

Despite it being chock-full of exciting, blood-boiling melodies and rhythms, with fine—if conventional—arias, duets, and ensembles, its initial success was never repeated, most likely due to its poor, and very depressing, libretto. Amalia, the Jenny Lind role, is a bore in every way except musically—all she does is complain and mourn—and the story is both a bummer and hard to relate to. The old Count Massimiliano Moor’s two sons are Carlo and Francesco: Carlo, the older, is courageous and intellectual (when we meet him in Act 1 he is quoting Plutarch!); Francesco is cruel and conniving. Carlo is away at university when he receives a letter purportedly from his father, which was actually written by the evil Francesco, telling him not to bother returning home. Furious, he convinces his fellow students to become bandits(!).

At home, Francesco has turned Massimiliano against Carlo and convinced an ally to claim that Carlo is dead so that he is now the heir apparent—there’s plenty of mustache twirling. Amalia, Carlo’s betrothed, is told that Carlo’s last wish was for her to marry Francesco. Massimiliano collapses and appears to be dead; when he is seen to be alive, Francesco hurls him into a dungeon. To make a long story short, Francesco is so evil and guilt-ridden that he dreams of the Last Judgment and asks a priest for forgiveness, which the priest denies; Carlo and his fellow thieves attack the castle; Carlo sets Massimiliano free, and Amalia is happy to see him but is miserable about him becoming a bandit and begs him to kill her, which he does, as Massimiliano watches and Carlo turns himself over to the authorities. When Francesco is last seen, he is railing against God. Huh? And the text itself, devised by librettist Andrea Maffei, is awkward and scans poorly.

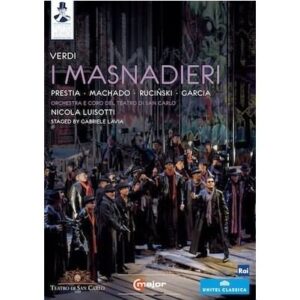

This compilation of performances in March, 2012 from Naples’ San Carlo serves the music handsomely. Tenor Aquiles Machado, whom I’d previously seen only in a well-sung but warped production of Tales of Hoffmann from Bilbao, is a splendid Carlo. His voice has grown since then, and he sings with passion, strong, centered tone, freedom at all registers, and utter commitment. And if he tires in the last act, it may be Verdi’s fault—the role is long and difficult. He may not cut a particularly heroic figure, but Carlo is at least part intellectual, so it works.

Artur Rucinski, a singer new to me, is remarkable as Francesco, a true Verdi baritone role. He’s made to be lame—hunchbacked and stiff-legged—as if his inward appearance were visible, which is hardly a necessary addition. Rucinski carries it off well enough and his singing is vital and expressive. Lucrecia Garcia is a vocal find as Amalia. The voice is big, bright, and agile; she, on the other hand, seems to be performing by rote and without direction or any subtlety in her phrasing. She gets most of the trills and coloratura and rides over climaxes well, but she’s emotionally detached. Giacomo Prestia’s Massimiliano is nicely sung and well-acted; he is victimized and sympathetic. The cast’s other standout is the Priest of Dario Russo, a comprimario role that nonetheless shows off a fine voice.

Neither the stage direction by Gabriele Lavia nor Alessandro Camera’s sets are worthy of either the opera or the musical performance. The set looks something like a seriously ruined old home, with no roof, dirt and leaves all over the floor, and dangerous-looking planks of wood—sort of like a run-down neighborhood. What does that have to do with the aristocracy? Or robbers (“masnadieri”)? Andrea Viotti’s costumes also are anachronistic (anachronistic with everything else on stage as well, not only with the opera and its presumed settings), with the robbers in long leather coats, sunglasses, and red scarves, and women at Francesco’s castle in tutus with pointy punk haircuts. There is a huge backdrop of a skull that reads “freedom or death”, and for Amalia’s prayer, a huge wooden cross descends into the midst of this mess. The characters’ gestures are stock opera behavior, save for Francesco’s lameness. All entrances are made from the center rear of the stage. You get the impression that the director simply despised the opera.

Nicola Luisotti’s leadership is excellent, from the warm cello solo that is featured in the prelude, through the introspective moments, to the angry confrontations, and the chorus and orchestra shine throughout. Luisotti has a fine sense that this opera is neither one of the truly “early” works, like Oberto or Alzira, nor as sophisticated as, say, Ballo or Forza. It is a work filled with conventional forms, but imbued with the energy of a professional, rather than a brilliant, novice.

The verdict? Well, I suspect that another video version of this opera will not come along for a while, and musically it is more than worthwhile, so it gets my recommendation. Subtitles are in all major European languages plus Korean, Japanese, and Chinese.