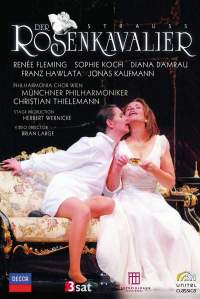

This 2009 production from Baden-Baden with the Munich Philharmonic finds both Renée Fleming and Christian Thielemann in spectacular form, with an assisting cast that is marvelous. Herbert Wernicke had directed Fleming at Salzburg in 1995; this performance seven years after his death, directed by assistants, remains a fascinating, unusual, but moving (and often very funny) staging. Wernicke, who also designed, used huge shifting mirrors to emphasize the importance of appearances in a story whose central character has an unusually acute self awareness and where the narrative tension is between superficial propriety and unmanageable sexual impulses.

Wernicke updates the opera to the early 1930s and adds a Pierrot who plays the role of the Moorish child who serves the Marschallin, and appears later, both at the start of Act 2 and to great effect at the very end. There’s no missing Wernicke’s insight. He and Fleming use as key the Marschallin’s remark that she feels the passing of time “mit gar so klarem Sinn”—too clearly, almost as pain. She takes us on this character’s journey from the teasing ageless lady lolling in bed (after what the prelude tells us has been a wild night with the 17-year-old Octavian, a wonderful Sophie Koch), to the mature woman on whom the events of the long first act wear viscerally.

Fleming’s Marschallin is impatient, smarter than the people around her, capable of a feline cruelty—and finally, deeply vulnerable. When in the final scene of the act she tries to explain what she feels to young Octavian, she lashes out with bitterness, even anger. This is played by her and Koch (supported with amazing flexibility by Thielemann) as a real scene, constantly changing, as the characters repeatedly reach out only to miss one another. Fleming’s Marschallin understands that she is asking a boy to somehow understand and, worse, comfort her about the inevitability of change. The boy is deeply hurt, not selfishly but because as played here, it is so hard to really understand the distress of another human being.

Wernicke’s staging is frank—Octavian in his underwear is lolling in an armchair with a post-coital scotch and cigarette at the opera’s start. But the Marschallin’s morning proceeds inexorably, the many visitors are wittily though broadly characterized. They include an Italian tenor (Jonas Kaufmann, no less), who arrives with press agent and photographers. The first verse of his song is sung straight (and spectacularly, with thrilling high B-flats and an easy C-flat). Then he gulps spaghetti! In the remaining acts the comic stretches are staged flamboyantly and are sometimes “naughty”; in Act 3 Wernicke introduces an interesting scene change—these are big choices, carefully worked out and very effective.

Thielemann points Strauss’ motifs with insight, handles the waltzes infectiously, and provides a ravishing sonority. He takes a big risk with the famous Act 3 trio, building it very slowly indeed; but the three women come through thrillingly. Fleming can float easy high notes, spin out long phrases on endless breaths, and call on a fully developed chest register—never needing to “sing speak” or bark as many do. Some mugging aside, Koch’s distinctive face and elegance are ideal; her voice is lovely, only occasionally stressed by some of Octavian’s high writing (the role was written for a soprano). Diana Damrau floats gorgeously through Sophie’s high lines and plays this (unexpected) spitfire with hilarious menace, directing killer glances at the otiose Baron Ochs, her father’s choice for her husband. Franz Hawlata is a capable Ochs but lacks a ripe tone. The supporting singers are wonderful: Franz Grundheber as Faninal is great, and Jane Henschel is a terrific Annina, just to mention two.

The Carlos Kleiber performance, from Munich, 1979 (DG) has breathtaking precision and clarity, yet he always maintains the illusion of spontaneity. The production is very traditional with some business and character choices that probably go back to the opera’s first years (he also takes the usual cuts, Thielemann does not). Like the conductor, Gwyneth Jones is a one-of-a-kind performer; here she sings lightly and mostly beautifully. Though she can assume the manner of a great lady, this Marschallin clearly was a tomboy, and remains one—it’s a performance of wonderful abandon and heart.

I wouldn’t want to be without these two DVDs, even simply to listen to, but Erich Kleiber’s spectacular recording on Decca (1954), and the film with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (now on a Kulter blu-ray), despite the lip-synching, are also self recommending.