It is very hard lately to get worked up about 14th century Swiss oppression by the Austrians. I recently realized that it wasn’t merely the fact that Rossini’s last opera, Guillaume Tell, was incredibly long, had too much dancing, and too many choral numbers, but that although all of the solos/duets/trios, etc., were magnificent, it is almost impossible to relate to what’s going on.

The Austrian Gesler is the governor of a couple of Swiss cantons, and along with his henchman, Rodolphe, and lackeys, is cruel and condescending to the Swiss. Guillaume Tell, Walter Furst, and Arnold Melchtal are Swiss patriots and conspirators. Arnold, problematically, is in love with the Habsburg princess, Mathilde (they met during an avalanche). Latish in the opera, when Tell refuses to bow to Gesler’s political demands, the latter forces Tell to shoot an arrow off of his son Jemmy’s head. That episode ends well, but Tell is imprisoned anyway, and in the last act Arnold becomes a leader of the rebellion and sets off to free Tell. A storm rises, and (off-stage) the boat on which Tell is being transported to his execution with Gesler aboard almost capsizes; Tell manages to leap off onto a rock (off-stage), and he takes up his trusty bow and arrow and (offstage) shoots Gesler dead. The sun comes with the announcement that liberation has arrived.

Graham Vick’s direction of the opera from the Rossini Opera Festival, abetted by Paul Brown’s sets, makes certain that we are aware of the politics, since even more, say, than Verdi’s Don Carlo, Tell is an opera about politics, with the love story almost parenthetical. Vick also manages to almost make us care about the Swiss, mostly through the dreadful, humiliating, inhuman behavior of the Austrians, throughout the opera’s four-plus hours. He has updated the action to the last years of the 19th century (or early 20th) and made the subject of class struggle a central point, often with unpleasant imagery and action. Arnold’s father, Melchtal, is murdered on stage.

Pointedly, the first act’s ballet (choreography by Ron Howell) is folksy and disorganized; the third-act dance sequences portray the aristocratic Austrians doing everything short of using the Swiss as footstools. Perhaps the finest thing about the direction is the manner in which the people are treated as individuals who eventually rise up as one to fight the Austrians. But Paul Brown’s white box of a set and some use of symbols keep the audience at a distance: Jemmy, alerting the revolutionaries in Act 4, is supposed to set fire to his house; here he lights a tiny fire on a table. Granted, one wouldn’t want to see a house fire, but there’s something ridiculous about miniaturizing the situation. When horses appear, they are life-size statues; background videos offer up nature in a guide-book sort of way. And a mammoth white staircase, unseen and unhinted at before, descends from the ceiling during the work’s divine musical apotheosis, for Jemmy to climb, presumably to a better Swiss future–an interesting image, but from left field. Repeated viewings make for a more coherent and exciting experience, by the way, but there is much here that is initially off-putting.

But all else being equal, this opera is nothing without great singing, particularly from Arnold. It is a bizarrely punishing role, even for Rossini: there are two high C-sharps, 28 high Cs, and an undisclosed number of Bs and B-flats, and many are with heavy accompaniment from the big orchestral forces. (This is the opera in which the high C from the chest was introduced–notes above G previously had been sung in a type of reinforced falsetto.)

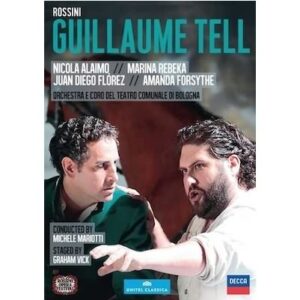

I cannot imagine a tenor today better equipped to sing this role than Juan Diego Florez, and he is indeed magnificent. The fact that he allows the high notes to be part of the vocal fabric rather than show-stopping moments is how Rossini wrote them–Florez’s sense of the musical line is superb. Of course he grandstands, but here he also seems genuinely involved in the character and drama, unlike, say, when he sings Arturo in Puritani, which is just a swashbuckling display of dizzying heights. And he has tamed some of the nasality of his tone; the sound is rounder and warmer than before. Quite a brilliant performance.

Although nobody else in the large cast is up to Florez’s vocal level, it might also be noted that they’re not required to be. Closest in showpersonship is normally Mathilde, and while Marina Rebeka has all of the notes, she’s also somewhat of a cold fish and the voice lacks warmth as well. I appreciate that she’s playing a Princess, but there’s a chill to her singing that goes beyond characterization. She doesn’t spoil anything, but she doesn’t add, either, and her French is execrable.

Nicola Alaimo is a wonderful Tell, and if the quality of the voice itself is not luxurious, his attention to detail, sheer musicality, and presence create a warm, father figure and rebel. Simone Alberghini’s Gesler is snarlingly sung and viciously acted, while the Hedwidge of Veronica Simeoni works well in the ensembles. Amanda Forsythe as Jemmy gets to sing an aria that Rossini himself cut early in the opera’s lifetime; it’s a pleasure to hear. The rest of the cast is splendid and very much in the moment.

Michele Mariotti’s leadership is exciting, precise, and wisely judged, giving the singers plenty of room to shine. There are chamber-like moments in this opera that are too often underplayed (the trio in the last act, for one); Mariotti draws attention to their beauty without exaggeration. And so: Not quite a production for everyone but one that exercises the mind and definitely has a point of view, with the musical side almost gloriously covered. Subtitles in English, German, French, and Korean.